This article discusses the environmental repercussions of the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian Territories and of its actions during the still-ongoing Gaza war.

Though a ceasefire has commenced – the third since the war began – Israel continues to kill Palestinians and to shell Gaza. And even if it holds, this cannot expunge the past two years of devastation and war crimes. These have turned the Gaza Strip “into a mass grave of Palestinians”.

Here, we will explore the environmental dimension of the Gaza war and Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian Territories.

Human and infrastructural cost of the Gaza war

Two hundred and fifty-one people were abducted during Hamas’ October 7 2023 attack on Israel, and around 1,195 killed: predominantly civilians, and including 38 children.

Hamas attack was an atrocity, however, lurid reports of systemic sexual violence and mutilations taking place during the attack have largely been found to be false, have been contradicted, or have not been proved beyond reasonable doubt; video and photographic evidence cited by Israeli politicians could not be found to exist; investigations were blocked and co-operation with inquiries refused by Israel; and videos released by Israeli security agencies showing alleged confessions to these actions were likely to have been produced under torture and therefore do not constitute credible evidence.

This did not stop such claims being “used repeatedly by politicians in Israel and the West to justify the ferocity of [Israel’s] subsequent bombardment of the Gaza Strip”. (Much “media coverage has also often failed to provide adequate context to the Hamas attack, suggesting it was ‘unprovoked’”.)

As a result, at the time of writing, at least 68,229 Palestinians have been killed during the Gaza war: 57 times the number of Israeli fatalities on October 7. This includes 463 deaths by starvation, as a result of the famine engineered by Israel’s deliberate blockade of humanitarian aid; at least 157 were children.

The use of famine as a weapon of war is a war crime. (See more key figures from the war here.)

A report based on figures leaked from a classified Israeli military database states that more than 80% of those killed by Israel in Gaza have been civilians. Such a high civilian death rate has only been recorded in modern warfare on three previous occasions, one of which was the Rwandan genocide.

As journalist Alona Ferber notes, “It should be possible to say two things at once […]: that Israel’s violence against Palestinians is unconscionable and so is the slaughter of Israeli citizens.” Nevertheless, Israel’s disproportionate response to October 7 has used it as a pretext for wiping out or removing the Palestinian population, as has been openly stated by members of the Israeli establishment:

- Aharon Haliva, former major general and commander of the Israel Defense Forces’ Military Intelligence Directorate stated that, “for every person [killed] on October 7, 50 Palestinians must die. It doesn’t matter now if they are children”

- In a radio interview, far-right Heritage Minister Amihai Eliyahu declared, “The government is rushing to erase Gaza, and thank God we are erasing this evil. All of Gaza will be Jewish”

- Ultranationalist Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, a self-described “homophobe, racist, [and] fascist”, was even blunter, asserting: “Gaza will be totally destroyed.” He is also reported to have said that the Gazan civilian population “can die of hunger or surrender. This is what we want.”

Israel has made good on these aspirations; as of July 2025, “at least 70 percent of buildings [in Gaza had been] leveled”. Roads have been severely damaged and “the healthcare, water, sanitation and hygiene systems have collapsed”. The majority of hospitals are no longer functional. By April 2024, almost 90% of “school buildings in Gaza ha[d] [already] been damaged or destroyed”.

Israel–Palestine power imbalance

In spite of the totality of this destruction, the international mainstream media fails to adequately represent the stark and fundamental power imbalance between Israel and Palestine, and the way that this manifests as a “structurally asymmetric conflict”.

This imbalance has been explicit in decades “of displacement and dispossession” for those in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. These “systemic structural inequalities […] were partly inherited from the colonial era and partly modified or created by Israel […] to maintain the control and power in the hand of […] the Jewish majority in [the country]”.

Israel is a socioeconomically Global Northern colonial power recognized by around 85% of the member states of the United Nations. Palestine is an occupied Global Southern state recognized by around 76% of UN members (in large part due to the US consistently blocking full Palestinian membership). In 2021, Palestine’s gross domestic product (GDP) was $3,464 per capita; in 2025, Israel’s was more than 16 times higher, at $56,435.

Palestine has existed under illegal military occupation by Israel since 1967, within an institutionalized apartheid system of segregation and discrimination, where restrictions on freedom of movement are used to “enforce [Israel’s] regime”, with travel permits only being issued “through a lengthy, non-transparent and arbitrary bureaucratic process”. Just 600 Palestinians were allowed to leave Gaza between March and May 2025, and only “after months-long efforts by humanitarian groups and foreign governments”.

Israel possesses “one of the best-resourced militaries” and “some of the most technologically advanced defences in the world”, including, as of 2023, 1,300 tanks and armoured vehicles, 345 fighter jets, “and a vast arsenal of artillery, drones and state-of-the-art submarines”.

It is also “one of the biggest exporters [of arms] in the world, selling […] to countries like Russia and the US”, while the latter – an ally with which it shares “strong historical and economic ties” – provides Israel $3.8 billion per year in military aid.

In addition, Israel has “covertly” amassed a nuclear weapons cache of around 90 warheads.

The Israel Defense Forces consists of 169,500 individuals, plus 400,000 reservists. The IDF estimated that Hamas’ armed forces in the Gaza Strip numbered around 30,000 prior to October 7. The weaponry Hamas forces possess includes “locally-made, improvised explosives”, with “the majority of its rockets […] [being] locally manufactured and technologically rudimentary”.

Drawing an equivalence between the two states and their respective military capabilities is clearly mendacious; the reality of the situation is that a highly militarised western state – which the International Monetary Fund ranks as among the 35 richest in the world – is occupying, oppressing, and decimating one which, by contrast, shares many characteristics with the world’s least developed countries (and where, by September 2024, “close to 100 per cent of Gaza’s population now live[d] in poverty, compared with 64 per cent before the onset of escalated hostilities”). As physician and author Gabor Maté has noted, “Unlike Israel, Palestinians lack Apache helicopters, guided drones, jet fighters with bombs, laser-guided artillery.”

This is not to excuse either party; like Israel, Palestinian forces have been guilty of war crimes. Yet the severity of this power imbalance is all too evident in Israel’s ability to raze Gaza with impunity. (After Israel broke the second ceasefire in March, it “effectively dropped the pretense that the Gaza offensive [wa]s primarily about freeing […] hostages […]. Yet impunity still reign[ed].”)

Since the Holocaust, the slogan “Never again” has been used as an injunction against both a second Holocaust against the Jewish people, and genocides against any and all other groups. Nevertheless, genocides have been carried out “time and again” – occurring on around 18 occasions since 1945. (Differing definitions mean there is no consensus about this number.)

Many organizations and experts in genocide law and international studies have asserted that Israel’s actions against Palestine meet the legal threshold of genocide, while South Africa brought a case before the International Court of Justice to this effect.

More recently, a UN Commission also concluded that Israel’s pattern of conduct, “including imposing starvation and inhumane conditions of life for Palestinians in Gaza”, does constitute genocide. The Commission also found that the “clear […] intent to destroy the Palestinians in Gaza” comes from the Israeli authorities’ “highest echelons”.

Environmental impacts

All of the above is to honor and acknowledge the devastating human cost of both the current manifestation of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict – and, indeed, the cost of all the conflicts that have occurred since the Ottoman Empire was defeated during the First World War, after ruling the region since 1517.

However, Israel’s actions have taken place within a broader system of violence, displacement, and exclusion overseen by Israel within its boundaries and in the Palestinian Territories which it occupies. This includes environmental impacts – and, in fact, damage inflicted upon the land goes hand in hand with the commission of genocide by Israel.

• Illegal Israeli settlements

Israel has militarily occupied the West Bank since 1967, when it seized the Palestinian territories from Egypt and Jordan during the Six-Day War: “the longest belligerent occupation in the modern world”. Settling this occupied land contravens Article 49 of the Geneva Conventions: legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war, making Israel’s settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territories a “flagrant violation of international law”.

In 2024, the International Court of Justice advised that the occupation itself is unlawful – a “historic vindication of Palestinians’ rights”. Later in the same year, the General Assembly of the United Nations called for Israel to end its occupation within one year, “both in law and in practice”. Yet the Israeli state “offers a slew of benefits and incentives to settlers and settlements”; in 2012, “every Israeli settler family in the Jordan Valley [wa]s given, in addition to an unlimited water supply, a free house, US$20,000, 70 dunnams (km²) of land, free health care and a 75% discount on electricity, utilities and transportation”.

Systemic violence committed by Israelis from illegal settlements, primarily in the West Bank, has been recorded since the early 1980s. From the turn of the millennium, that violence has steadily increased: a war that is “quieter” than that in Gaza, but which is nevertheless escalating due to “a confluence of ideological fervor, opportunism and far-right Israelis’ political vision for the region”.

‘Rampages’ – including ones in 2008 which Israel’s then acting prime minister, Ehud Olmert, described as “pogroms” against West Bank Palestinians – have included arson, the killing of thousands of livestock, and the murder of Palestinian civilians. Increases in harassment, trespass, intimidation, and violence by carried out by settlers against Palestinians coincided with the election of the current government – “the most rightwing and anti-Arab government in the country’s history” – and the start of the Gaza war, with “settlers […] act[ing] with near-impunity”.

In 2023, Israeli forces and settlers undertook “12,161 attacks against Palestinians and their properties, including 3,808 against properties and religious sites, 707 against lands and natural resources, and 7,646 against individuals”. Consequences included damage inflicted on approximately 21,700 trees (nearly 19,000 of which were olive trees).

More specifically, between October 7 2023 and November 1 of the same year, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs documented 171 settler attacks against Palestinians, with “Israeli forces accompan[ying] or actively support[ing] the attackers” in almost half of these cases. Also since October 7, the Israeli national security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir – himself a settler, with a background in Kahanism, “a violently racist movement that supports the expulsion of Palestinians from their lands” – “distributed semiautomatic rifles and other weapons to settlers and far-right Israelis, which are now being used against Palestinians”. One hundred and twenty thousand firearms had been distributed by October 2024.

Israeli misappropriation of Palestinian land has always occurred via both ‘official’ mechanisms and settler violence, yet these are both manifestations of state violence: “a coordinated pincer strategy to entrench Jewish control over the West Bank”, with the Israeli regime “actively aid[ing] and abet[ting] the settlers’ violence”. And, increasingly, “the line between settlers and the army [is] blurring”, with the impacts upon Palestinians including:

- Displacement from their homes

- Restrictions on movement

- Population decreases

- “Crops destroyed by arson attacks, physical sabotage or by settlers grazing flocks on land that Palestinian herders had relied on”

- Water sources being “polluted, vandalized or taken over”

- Difficulties accessing health services and education (in Gaza, it is thought that lack of access to education may create “a lost generation of permanently traumatised Palestinian youth”, but the same could be true of the West Bank)

- Not being able to remain self-reliant, leading to the selling of livestock or borrowing of money

- Demolition of existing buildings and prohibitions on building new ones

- Land confiscations (sometimes imposed punitively).

Military and settler violence has caused the deaths of upwards of 1,000 Palestinians in the West Bank since October 7, 2023.

Moreover, Palestinian police “are barred from responding to settler violence”.

• Environmental harm caused by settlers

Within this extreme colonial violence, where “all lives are precarious—people, flora, fauna—and [even] the air, water, and land”, it is unsurprising that “a litany of […] land degradation [has also been] caused by Israeli settlers on Palestinian land”.

Researcher Dror Etkes, who has “ke[pt] close tabs on the expanding Jewish settlements” for more than 20 years, states that this includes “settlers […] dumping trash [and] spoil”, and allowing wastewater to flow directly onto the land. In the words of Yousef Abu Safieh, the Palestinian Authority’s environment minister, “Israel not only exploits Palestine’s resources, it also pollutes and destroys them.”

A report published by the Norwegian Refugee Council, primarily assessing the effect of Israeli settlements’ wastewater discharge, updated in 2024, lists other harms caused by Israel illegal settlements in the West Bank.

The degradation of Palestinian land – which demonstrates Israel’s disregard of the Geneva Convention’s stipulation that, as occupier, it should act as custodian of them – stands in stark contrast to the “great care [that the Israeli government takes] to guarantee that its citizens enjoy the benefits of a clean and comfortable environment”. This inequality is felt by neighbouring Palestinian communities in the form of health concerns; contamination of agricultural lands, with deleterious effects on crop viability and marketability; and ecosystem disruption, including the introduction of invasive species.

In addition, “Israel covertly transports waste products from its own country into dumps and quarries throughout the occupied West Bank […] – deliberately poison[ing] the water, land and livestock of nearby Palestinian villages.”

Solid waste from Israeli settlements – which produce considerably more per capita than those of the Palestinians – is also “contribut[ing] to [a] strain on West Bank solid waste management capabilities”, where management of solid waste is limited by “weak technical expertise […] and lack of financial resources”. Reliance upon the burning of waste – already unsuitable given the quantity generated annually (around 250 thousand tons) – releases toxic gases, among other environmental problems. In addition, “hundreds of thousands of tons of hazardous waste” dumped in the West Bank by Israeli chemical and military industries “constitute severe […] health and safety hazards to nearby Palestinian cities and communities”.

Also, as of 2018, seven industrial zones and 200 factories had been moved from Israel to the West Bank, or built there, taking advantage of cheaper labor, and more lenient environmental regulations, where “it applies less rigorous regulatory standards […] than […] inside its own territory” – an “abus[e] [of Israel’s] status as an occupying power”.

Certain factories were specifically transferred to the West Bank “due to [their] carcinogenic chemical emissions”. This includes the Dixon Gas industrial factory, solid waste from which “is burned in [the] open air”. Israel also disposes of its hazardous waste in more than 50 locations across the Occupied Palestinian Territory, causing concomitant increases of “a number of mysterious diseases and cancers”.

Given Israel’s continued illegal settlement, the combined settler population of East Jerusalem and ‘Area C’ (which consists of more than 60% of the West Bank, and which is completely controlled by Israel)

is anticipated to reach one million in the next 10 years. The approximate current total population is around 730,000; an increase of a factor of almost 14 will have a “vast” environmental impact. (Israel’s population has already increased sixfold between 1967 and 2012: a period of rapid industrialization which made “environmental woes” inevitable.)

Meanwhile, in Gaza in April this year, where “many people [were] forced to live in tents erected amid piles of garbage” which have become breeding grounds for rats, snakes, and disease-carrying insects, Palestinians were reported to be “suffering from extremely dire health conditions”. This is further compounded by the decomposition of bodies trapped under rubble, and the difficulty of burying animal corpses during Israeli bombardment.

The destruction of sewage infrastructure has, additionally, “caused sewage floods in the streets, turning them into health hazards and dangerous swamps”. The danger of “toxic and hazardous chemical substances […] seep[ing] into the groundwater reservoir” could make drinking water into “a deadly poison”. At this time, Israel also cut power to the Deir Al-Balah water treatment in the centre of the Gaza Strip.

• Impacts from munitions

Israel uses ammunition and tank shells containing depleted uranium against Palestinian citizens (and elsewhere); this causes various cancers, chronic diseases, and fetal malformations in affected populations. “Both chemical[ly] and radiological[ly] toxic”, depleted uranium – a by-product of uranium enrichment, a process with applications for both fuel for nuclear power reactors and for nuclear weapons – may contaminate soil it falls upon.

Israel has also used white phosphorus in both Gaza and Lebanon. This chemical incendiary ignites when exposed to oxygen, burning at 1,499°F (815°C). The thick smoke it produces may be used to mask military operations, but the substance “also inflicts horrific injuries”, “pos[ing] a high risk of excruciating burns and lifelong suffering”. Due to its high solubility in fat, white phosphorus can “burn people, thermally and chemically, down to the bone” and cause multiple organ failure by entering the blood. Dressed wounds may “reignite when […] re-exposed to oxygen”. Even relatively minor burns frequently prove fatal, while extensive scarring which tightens muscle tissue can cause physical disabilities in survivors, who also face not only the initial trauma but painful treatment and “appearance-changing scars [which may] lead to psychological harm and social exclusion”. Providing treatment also “exacerbate[s] the already challenging process of treating serious burns”.

The use of white phosphorus against civilians violates international humanitarian law.

As well as potential for the fires it causes to destroy buildings, property, and crops, and to kill livestock, its use can also result in pollution to groundwater, marine environments, and agricultural settings, and the destruction of wastewater treatment plants. Animals can also die from its inhalation, or by eating contaminated vegetation.

• The West Bank barrier

Begun at the turn of the millennium, the 440 mile (708 kilometer) West Bank barrier partly follows the 1949 Jordanian–Israeli armistice line, but at other points stands within the West Bank, isolating around 25,000 Palestinians from the rest of the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

Its location means that Palestinians lost their access to 23 wells and more than 50 springs. It has also fragmented ecosystems and “create[ed a] new climatic and environmental status”, including the accumulation of rainwater on one or other side, causing soil erosion. Its construction also led to “the extensive contamination of natural habitats associated with the use of heavy machinery and millions of tons of concrete”.

Additionally, the borders of Gaza – “hardened and heightened into a sophisticated system of under- and overground fences, forts, and surveillance technologies” – have also seen a ‘buffer zone’ established on the Palestinian side. From 2014, the Israeli military’s “clearing and bulldozing of agricultural and residential lands […] has been complemented by the unannounced aerial spraying of crop-killing herbicides”. The spraying takes place “during key harvest periods, targeting spring and summer crops”, employing three herbicides: glyphosate (formerly marketed by Monsanto, and now by Bayer, as Roundup), oxyfluorfen, and DCMU: “probabl[e]”, “possible”, and “known/likely” human carcinogens, respectively. Consuming the meat of livestock which have themselves consumed contaminated plants can indirectly cause “long-term negative effects” for humans.

This practice – described by Forensic Architecture, an interdisciplinary research agency which investigates state and corporate violence, as the “weaponis[ation of] herbicide spraying” – has rendered swathes of formerly arable land barren. Not only has this destroyed Gazan farmers’ livelihoods, but left “farmers, youth and families, further exposed to Israeli fire from hundreds of metres away”. As of 2012, “no Palestinian farmers have ever been compensated for damages to their crops”.

In addition, since October 2023, “Israel’s ground invasion [of Gaza] […] systematically targeted agricultural farmlands and infrastructure”. In September 2024, the United Nations Satellite Centre reported that almost half of Gaza’s agricultural land had been destroyed.

• Wastewater discharge

Wastewater is the most severe problem facing the Palestinian water sector after water scarcity, which is itself “used by Israel as a tool of oppression”. After occupying the Palestinian Territories in 1967, Israeli military authorities have since remained in control of “all water resources and water-related infrastructure”, and “continues to control and restrict Palestinian access to water […] to a level which neither meets their needs nor constitutes a fair distribution of shared water resources”. This constitutes “an instance of environmental racism at its worst”.

In the same year, Israel prohibited Palestinians from “extracti[ng] […] water from any new source or […] develop[ing] […] any new water infrastructure” without a permit – which are “near impossible to obtain”. Palestinians are also unable to access the Jordan River, while cisterns for the collection of rainwater are frequently destroyed by the Israeli army. Just 37% of Palestinians received sufficient quantities of water in 2012, yet Israeli water companies charged Palestinians 11 times as much for water as nearby Israeli settlements. In 2017, 180 Palestinian West Bank communities had no access to running water, with even towns and villages connected to the water network unable to rely upon a consistent supply.

Israeli settlers, on the other hand, face no restrictions in their access to Israel’s own West Bank water network, which the state-owned Israeli water company Mekorot feeds from wells sunk and springs tapped for the benefit of Israelis alone. Israel not only controls Palestinians’ water in the West Bank, but each “Israeli settler [consumes] four times the amount consumed by [one] Palestinian”. As a result, such wells that remain accessible to Palestinians “have suffered drastic decreases in their output”.

Many Palestinian communities are therefore reliant on “overpriced and often unsanitary water tankers” which they “must travel across a desert, criss-crossed with Israeli checkpoints, to bring home” – meaning that water may cost families as much as half of their monthly income. And, still, Palestinians often consume “dramatically less than [the amount] the […] World Health Organization recommends as the minimum quantity for basic consumption”.

Since 2022, Israel has been ranked just behind the US in the UN’s Human Development Index, which assesses national populations’ longevity, health, and standard of living. As a result of leading lifestyles typical of the Global North, “Israeli settlers in the West Bank […] produce similar amounts of wastewater to the Palestinian population, despite being outnumbered more than six to one.”

In 2018, it was established that, of all wastewater discharged by Israeli settlements – which amounted to around 131 million cubic feet (40 million cubic meters) per year – 90% was not only discharged onto Palestinian lands, but without any form of treatment.

Settlements are most often located on high ground, “for reasons including surveillance and territorial dominance”, meaning that “lower-lying Palestinian communities, their agricultural lands and natural water systems” are particularly at risk from these discharges. More than “2 million cubic metres [6.6 million cubic feet] of raw [untreated] sewage flow[s] into the valleys of streams of the West Bank…[causing] severe damage […] [and] the contamination of mountain groundwater”.

In addition, “waste products, generated from the production of aluminium, leather tanning, textile dyeing, batteries, fiberglass, plastics and other chemicals [in Israel’s industrial facilities in the West Bank], [are allowed to] flow freely down to Palestinian villages in surrounding valleys”. Industrial wastewater has been found to contain “a high concentration of chemical materials [which] leach […] into the soil and groundwater resources”.

Water sources to which Palestinians are allowed access to are primarily surface and groundwater sources, with “the most important sources [being] rain, runoff, groundwater, and springs”. Therefore, pollution from wastewater “aggravates the chronic drinking-water shortage in Palestinian communities in the West Bank”, and, in 2001, the Palestinian Ministry of Health connected contamination from wastewater with “frequent outbreaks of intestinal diseases in the West Bank”. However, because settlers use Israel’s water-supply system, they remain unaffected by the consequences of their own wastewater.

Such contamination also affects crops – “a major sector of the Palestinian economy”. Raw wastewater will ultimately also reduce land fertility, as well as:

- Driving the concentration of nitrates and salt, raising soil salinity

- Reducing vegetation

- Driving desertification

- Decreasing biodiversity

- Causing pests and insects to proliferate.

In addition:

- The contamination of Palestinian water by wastewater has been further enabled by Israel’s “neglecti[on of] wastewater management and refus[al to] […] expan[d] […] new wastewater networks to meet the growing population”. Over-pumping of underground aquifers, all of which are “monopolised by Israel”, has caused the intrusion of saline water into the groundwater table

- The average flow of the Jordan River, “an international river basin unilaterally monopolised by Israel”, has been reduced from 4,101 million cubic feet [1,250 million cubic meters] per year in 1953 to 499-666 mcf [152-203 mcm] due to the effect of two huge reservoirs. It was also deemed unsafe for Christian baptism in 2010, due to its pollution by Israeli settlements and industry run-off

- The Dead Sea – also subject to pollution – “is dying”, its level dropping by almost four feet [1.2 m] every year. Having shrunk into two separate sections, its banks are collapsing, and sinkholes are opening up, all as a result of “the freshwater sources that feed [it] [being diverted] for drinking water and irrigation”, while “its salts are pumped by Israeli companies to flood the global market with exotic cosmetic products”

- Dozens of springs located on private Palestinian land, used for irrigation and watering livestock have been seized by settlers and “turned […] into tourist attractions and swimming pools”.

Israel’s growing population and rising standard of living means that it is confronted by both severe water shortages and “persistent contamination of the existing water thanks to rampant ‘development’ and industrialization”. The country carried out expensive cloud-seeding experiments for seven years, and is considered a world leader in desalination and water recycling – yet continues to “destroy […] the rain-water cisterns and wells of agrarian Palestinian villages”.

• Destruction of olive trees

Chief among environmental impacts, in the case of Israel–Palestine, is a long history of both Israeli settlers and the military purposefully “hack[ing] to pieces”, “spraying […] with toxic gases”, and “uproot[ing] olive trees […] as part of the[ir] country’s efforts to seize Palestinian land and forcibly displace residents”. Three million trees (including olive, but also citruses) were torn up between 2000 and 2012. Three thousand, one hundred olive trees alone were destroyed by Israeli settlers in the occupied West Bank during the 2024 harvest alone. “Practically no […] complaints filed” in relation to attacks on West Bank Palestinians’ trees have led to an indictment.

In August this year, 3,000 more, in a village near Ramallah, also in the West Bank, were destroyed by the military, who claimed them to pose a “security threat” to an Israeli settlement road. In the same month, 10,000 trees, some of which were 100 years old, were bulldozed by the Israeli army, explicitly in order to make a village “pay a heavy price” after “reports that an Israeli settler had been attacked near[by]”.

Increased instances of the Israeli military setting roadblocks, checkpoints, and curfews, have further hampered farmers’ work, with those close to Israeli settlements “hav[ing] to apply for permits to enter their [own] land”. In 2023, access being denied by Israel led to the loss of approximately 1,365 tons of olive oil, at a cost of some $8.5 million (at 2024 prices).

These actions – plus “the burning of ancient trees and theft of both olives and young saplings” – comprise just a fraction of Israeli military and settler violence, which, since the beginning of the war on Gaza, has “surge[d]” in the West Bank. B’Tselem, the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, has collated hundreds of reports of beatings, restrictions on movement, home demolitions (including punitive demolitions and forced “self-demolitions”, which cost less than waiting for the Israeli government to carry them out), and other abuse on an interactive map of the Territories, which gives some indication of the scale of these actions. As of 23 August 2025, this includes “at least 671 Palestinians, including 129 children” being murdered by Israeli forces or settlers, and “tens of thousands of Palestinians hav[ing] been forced out of their homes”.

In the Gaza Strip alone, “more than one million olive trees [were] uprooted” between October 2023 and September 2024, while only four of 37 olive presses in the Strip remained functional at that time – though lack of access to fuel means that even those which remain may not be usable.

Olive trees – a “maltreated symbol in [an] occupied land” – are highly significant to the Palestinian people, both symbolically and economically: they are mostly indigenous, long-lived, and occupy almost half of the agricultural land in Gaza and the West Bank, where villages often rely almost entirely on agriculture and livestock for income. As of 2019, as many as “100,000 Palestinian families [were] estimated to rely on these trees as a source of income”. Olive oil is crucial to the Palestinian national economy, while olive production “mak[es] up 25% of the total agricultural production in the West Bank”.

The olive tree was also voted Israel’s national tree in 2021, and symbolizes longevity and peace in Judaism (as it does in the other Abrahamic religions), due to its part in the Noah flood myth. In the Hebrew Bible, “a dove returns to the ark with an olive leaf in its beak, signaling the end of God’s judgment through the flood and the restoration of peace on earth”.

In fact, as well as breaching the Paris Protocols, the Hague and Geneva Conventions, and the International Covenant on Economics, Social and Cultural Rights, Israel’s arboricide even contravenes the Halakha, Jewish religious laws which state, “Even if you are at war with a city … you must not destroy its trees.”

Destroying these trees – as well as “blocking and preventing Palestinians from accessing their farms and water sources[, which] means more food and water insecurity” – has nevertheless been used by Israel as a method to displace Palestinians and steal their ancestral lands since 1967. Yet these “practices […] have become harsher and more malicious […], with some areas being classified as ‘state land’ to facilitate theft”.

The registration of West Bank land ceased in 1967, yet unregistered land still comes under the Ottoman Land Code of 1858. Jordanian and British governance “interpreted [the 1858 code] such that cultivating land for 10 years gave the farmer rights to it that remain even if cultivation stops”. Israel ‘reinterpreted’ the “code to mean that if cultivation ceases after 10 years, the land goes to the state” – meaning that “the absence—and destruction—of Palestinian olive trees are crucial for Israel to grab land ‘legally,’ making their very presence a threat to Israel’s expansionist ambitions”. (Whereas, illegal settlers have been quoted as saying that they “definitely planted [olive] trees only for the purpose of seizing land”.) Limiting farmers’ ability to work their land by illegalizing their access to it, and via inconsistent bureaucratic barriers and violence, enables “Israel’s deliberate confiscation of agricultural lands”. In 2023, “Israel […] seized more Palestinian land than in any year in the past 30 years”.

A ‘co-ordination mechanism’, developed and managed by the Israeli army, ostensibly “protect[s] Palestinians from settler violence and enable[s] a safe harvest”. This is not the case in actuality: dates may be set without taking farmers’ needs into account, while, during the 2024 harvest, there was frequently no co-ordination at all. Dates which were issued were “communicated […] to Palestinian residents haphazardly and last minute”. Frequently, Palestinian council heads were only given one day’s notice, and just one or two days to carry out the harvest: “neither enough time to prepare for the harvest, nor complete it”.

Palestinian farmers were also barred from accessing their lands, meaning that settlers instead harvested these private Palestinian lands. These crop thefts occurred more frequently in 2024 than in previous years, with Israeli soldiers or security forces failing to intervene. In other cases, Palestinians were unable to harvest at all due to “settlers […] confiscat[ing] their ID cards”, “Israeli soldiers and settlers assault[ing] them, forc[ing] them out of their lands or otherwise obstruct[ing] them”, including Palestinians being shot at. A 59-year-old grandmother, a resident of the Palestinian village of Faqqu’a, was shot dead by an Israeli soldier while setting out to harvest olives on her own family’s land.

In all, 113 “separate incidents of violence, harassment, harvest thwarting or damage to olive trees and crops involving Israeli civilians and soldiers” were verified by Yesh Din, an Israeli organization which monitors and reports on human rights abuses in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, between October 1 and November 15 2024.

The Israeli state and military have even been documented stealing Palestinian-owned olive trees and saplings, while “trees older than the state of Israel have been uprooted from Palestinian lands and replanted in Israeli cities to beautify public spaces”. “Grand old trees” are even reported to be highly sought by “the immoral wealthy” to “adorn […] the gardens of their villas”.

All of these factors “further undermine the food sovereignty of Palestinian families and are yet another attack on Palestinian self-determination”.

They also mean that harvest time, formerly characterized by “community gathering and cooperation” and “nothing short of a festive season”, “a cherished time with extended family and friends coming together to pick olives, drink tea and share food under the trees[,] has become increasingly dangerous”. This disruption, not only of Palestinian livelihoods but of cultural continuities, also means that younger generations are denied participation in age-old agricultural practices, curtailing traditional ways of life.

Yet, olive trees’ historic “rootedness in the land” – and the ability to sprout again as long as their roots remain intact – makes them “one of the most evocative symbols of resilience, and representative of a generational bond with the land”. This is reflected in the Arabic word sumud – ‘steadfastness’ or ‘perseverance’ – which Palestinians use “to refer to their commitment to stay rooted to the land and defy all Israeli attempts to drive them out”. Due to their longevity, many olive trees embody a “symbolic value as witnesses and sites of memory of the ongoing Nakba [or ‘catastrophe’; the mass displacement and dispossession of Palestinians] and the many Intifadas [Palestinian uprisings against the Israeli occupation] [which] the land has experienced”. However, in Gaza, deprived of fuel and food, “families [have been] forced to destroy their trees in order to have firewood for survival” – trees which are seen as akin to friends, children, or “life companions”.

Olive trees also “expose the lie that Israelis came to an empty land”, countering “Zionist slogans like ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’”. (As part of the agriculturally productive Fertile Crescent, “the region has been home to some of the earliest agricultural societies and thriving civilizations”.) One tree, near Bethlehem, is thought to be as much as 5,000 years old, making it one of the oldest in the world, and meaning that it pre-dates the Abrahamic religions of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.

But the Palestinian people’s olive trees also relate not only to “their relationship to their ancestors [but] to their future”. Therefore, even in the face of restricted access and settler attacks, “Palestinian farmers are determined to remain steadfast”, braving dangerous areas to farm their olive trees, “to prove they won’t be defeated”, and continue to replace those which are uprooted, “viewing them as a statement of hope, perseverance, and their unwavering connection to the land”.

• Afforestation

Due to olive trees’ significance within Judaism, Jewish people immigrating from Europe at the turn of the 20th century sought to “ideologically and literally ‘root’ the[selves] to the new/old homeland” through agricultural work which included planting their own olives. However, despite being supported by collectives like the Lovers of Zion, the Jewish Colonization Association, and wealthy individual funders such as banker-philanthropist Baron Edmond James de Rothschild, these early settlers had no experience of farming Middle Eastern terrain, and olives’ labor-intensivity and bitter taste limited their enthusiasm.

They therefore “dismissed centuries-old sustainable Palestinian agricultural practices as ‘undeveloped’, and […] [instead] used sophisticated European steam engines, mechanised ploughs, reapers and threshers to develop capital-intensive vineyards and cash-crop plantations for commercial marketing”. They sought “to birth themselves […] anew as an ecologically integrated, utopian socialist community” – yet this “ecological zeal” manifested itself not through “respect[ing] and adapt[ing themselves] to the land, but [by] subjugat[ing] and transform[ing] it”.

The significance of olives for Palestinian culture and heritage, and their adoption as an emblem of anti-occupation resistance, further reduced the trees’ appeal as a Zionist symbol. Instead, the Jewish National Fund (the JNF; founded in 1901 and still active) carried out “extensive land acquisition and ‘afforestation campaigns’” instrumental to the creation of both Israel and Palestine’s contemporary landscapes. This saw the introduction of, predominantly, pine trees (including non-native species). Over the years, the Fund has planted over 240 million trees in the region.

Ideological critics describe this project as colonialist, while environmentalists highlight how monocultural planting “diminish[es] biodiversity and increas[es] the risk of forest fires” (“devastating” fires in JNF forests in 2010, 2016, and 2021 caused the deaths of both people and animals and the destruction of homes). Afforestation by the JNF in southern Israel has also been the cause of violent protests because the planting threatens Bedouin tribes’ livelihoods by diminishing their ability to farm and graze livestock. (The JNF’s ongoing Blueprint Negev project, which “seeks to develop reservoirs, pine afforestation and water conservation programs in the Negev desert” will come at the cost of upwards of 150,000 Palestinian Bedouin, “whose ‘unrecognised’ villages, as a direct result of Israel’s policies, already lack electricity, running water and sewage disposal”.)

Much JNF planting is carried out by volunteers, who feel “a […] connection” with the trees and may return to visit them. Meanwhile, people in the Jewish diaspora donate towards the JNF, “affirm[ing] [their] ethnic nationalism by helping [to] ‘plant a tree in Israel’”: “a tangible symbol of their emotional and financial investment in [the country]”.

Pines were chosen by the JNF because they “reminded [its] leaders of […] their homelands in snowy Europe”. (A 2013 promotional article on the organization’s website proclaimed that the German Black Forest “has got nothing on us”, and Carmel National Park, partially located on the site of the destroyed Palestinian village of al-Tira, is nicknamed ‘Little Switzerland’ due to its alpine appearance.) This “creat[ed] a European-modeled landscape” which “conceal[ed] the geographical dislocation experienced by the predominant Ashkenazi Jews”.

The majority of the pines planted by the JNF are Aleppo pines, a species native to the region, but its range has been “extend[ed] […] beyond any previous point in history” by intensive planting. And with dense crowns that shut out light, and a thick blanket of its acidic shed needles, which prevents most other plants from growing, they lead to low biodiversity and “ruin […] the livelihood of Palestinian shepherds, whose animals depend on grazing land”.

Furthermore, in contrast to one of Israel’s founding myths – that the country ‘made the desert bloom’ – in some places its practices are instead driving desertification. The planting of thousands of non-native eucalyptus trees in the swamps of southern Palestine, for example, “dried out all of [the area’s] ancient water wells and other water sources”. Elsewhere, between 1971 and 1999, “the extensive spread of settlements and military bases[,] alongside Israel’s pervasive bombing”, caused the loss of 95% of Gaza’s forests. The theft of large areas traditionally used by Palestinian for grazing means that the land remaining available for this purpose is now subject to overgrazing, and therefore also under threat of permanent desertification.

Contemporary Israel depicts itself as “a ‘green democracy’, an eco-friendly pioneer” – proud to be “the only country in the world that will enter the 21st century with a net gain in numbers of trees” – yet this greenwashing obscures the role that its ostensibly environmental actions play in its project of land seizure and Palestinian displacement. The JNF “promotes an exclusionary, discriminatory brand of environmentalism” via a constitution that “explicitly state[s] that its land cannot be rented, leased, sold to or worked by non-Jews”. The majority of sites where JNF planting has taken place “conceal[s] the bulldozed houses and torched groves of Palestinian villages”, meaning that this afforestation by fast-growing pines has prevented Palestinian return, while also “play[ing] a role in Nakba denial and the erasure of Palestinian history and collective memory”.

Both the destruction of existing olive trees and afforestation “transform […] the occupied landscape and its ecology”: ecological imperialism, whereby “not just people but their landscapes and environment” are dominated. By 2012, “indigenous arboreta [already] ma[d]e up only 11% of Israeli forests, and pre-1948 growth account[ed] for only 10% of Israel’s greenery”.

Similarly, by 2015, Israel had created 81 national parks and 400 nature reserves: spaces often used historically “to displace indigenous peoples from their lands and ecosystems under the guise of ecological conservation”, “reinforc[ing] the division between subjects and citizens”. In this case, “the administration of nature advances the Zionist project of Jewish settlement alongside the corresponding dispossession of non-Jews from the[se] space[s]”.

This use of land management as a tool of oppression can also be seen in projects such as “the ethnic cleansing and ecological degradation” that occurred at Lake Hula in northern Israel. In 1933, the Ghawarani tribe – who had inhabited the area for 200 years – was evicted from this, “one of the oldest documented lakes and wetlands in history”, by the Palestine Land Development Corporation, using funds from both the JNF and private sources. In 1950, the JNF drained the lake, “ignoring the warnings of scientists that the peat soil under the swamps would not make fertile land”, and without having assessed potential ecological repercussions.

The resulting environmental catastrophe saw the wetlands’ unique ecosystem destroyed, and, “despite one JNF hydrologist’s certainty that ‘our peat is Zionist peat … our peat will not do damage’”, its decomposition released pollutants into local rivers and lakes, “creat[ed] crop-damaging black dust and ma[de] large tracts of land susceptible to damaging underground fires”. At a cost of $23 million, a small area of this depopulated region was partially re-flooded in the 1990s.

The future

These environmental impacts are inextricably entangled with the subjugation of the Palestinian people, and exist within a broader system of violence, apartheid, displacement, and exclusion overseen within Israel’s boundaries and in the Palestinian Territories which it occupies.

As talks continue – a “conversation between the sword and the neck”? – Israel must be held accountable.

Additional material

Genocide & Ecocide: The Interconnected Crimes Against Humanity & Nature: a talk with Professor Mazin Qumsiyeh.

Organizations to support

- Many charities, like Ele Elna Elak, are providing emergency relief. You can find further trusted organizations in lists here and here. You can also use the Gaza Family Funds Directory to make donations directly to those in need of support

- Grassroots organization the Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC) works “to rehabilitate lands destroyed by the Israeli occupation, preserve native seeds and support farmers”, and runs an Olive Harvest Campaign which allows volunteers to assist farmers during the Palestinian olive harvest, which speeds up the process and “can dissuade settlers from attacks”. You can donate here

- The Israeli Rabbis for Human Rights has also formed human shields as a direct action to protect Palestinian farmers from settlers’ attacks during the harvest season. Faz3a, a Palestinian-led initiative named for a colloquialism for “reinforcement”, has also helped more farmers to harvest their olives, by “mobiliz[ing] a mass presence of internationals on the ground, […] to dissuade settlers from hassling Palestinian farmers”

- The Palestinian Fair Trade Association (PFTA)’s Trees for Life project “promotes sustainable agriculture and supports farmers across the West Bank” and “has replanted thousands of olive trees in Palestine”. You can support the PFTA’s olive tree-replanting efforts here, via the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights (USCPR)

- A regeneration project run by the Arab Group for the Protection of Nature, the Million Tree Campaign, “plants fruit, nut and olive trees across the West Bank […] [,] plant[s] crops, rehabilitate[s] greenhouses and help[s] poultry farmers and fishers in Gaza”. More than 99,000 trees and 970 dunums of crops have been planted, despite settler aggression and Israel’s access and water restrictions. Donate here

- Seeds of Resilience, an “initiative […] powered by young people from Gaza”, “fight[s] hunger with [its] secret weapon: seedling[s]”. Donate here

- The Palestine Heirloom Seed Library conserves and protects indigenous seed varieties passed down through generations, alongside heritage, culture, and biodiversity, while working with Palestinian farmers who are still maintaining these seeds in situ. Donate here.

Organisations to boycott and divest from

Boycotts have been successful historically in forcing policy change, such as in relation to apartheid in South Africa. This form of non-violent direct action exerts economic pressure on specific companies and the Israeli economy in general, challenges Israel’s international standing, and raises awareness and expresses solidarity with Palestinians (read more).

Consider boycotting:

- “Companies […] no longer merely implicated in occupation – [but which] may be embedded in an economy of genocide” – found by a UN report to include IBM, Microsoft, and Amazon; Chevron and BP; Caterpillar, Hyundai, and Volvo; Airbnb and Booking.com; and the UK’s Barclays bank. US multinational investment companies BlackRock and Vanguard are the main investors in a number of these companies

- The banks which finance Israeli settlements, weapons, and military, which include HSBC, JP Morgan Chase, the Lloyds Group, the NatWest Group, and the Santander Group. Also consider which company your workplace banks with

- UK Local Government Pension Schemes and universities which invest in companies complicit in Israel’s violations of Palestinian rights and of international law

- Organisations “implicated in the commission of international crimes connected to Israel’s unlawful occupation, racial segregation, and apartheid regime”, targeted by Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions, a three-pronged, Palestinian-led movement. These include Reebok; Intel and Dell; the AXA insurance corporation; and more. Donate here

- The (as of 2023) 51 businesses specifically complicit in Israel’s illegal settlement enterprise, including Motorola Solutions, Puma, Siemens, and Tipadvisor

- Companies involved in the Gaza war, which include Google

- Companies which have provided Israel with weapons and other military equipment used in its attacks on Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, and Syria since October 2023, which includes Amazon, Boeing, Cisco, and Ford.

You can also use apps such as NoThanks and Boycat to check whether products you’re purchasing are produced by companies which support Israel’s actions.

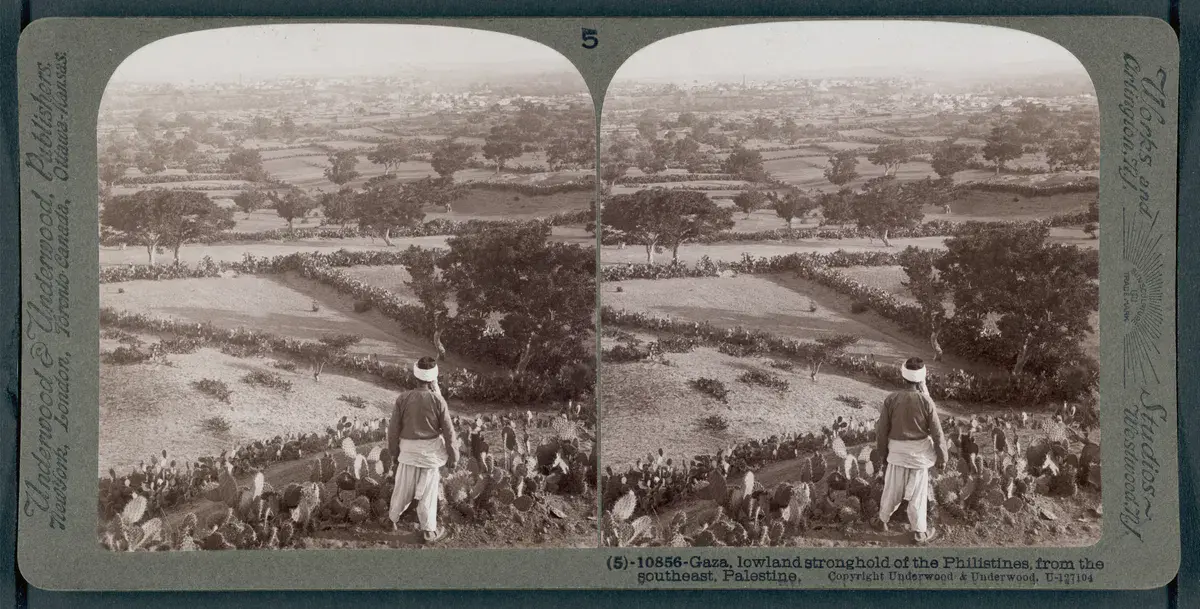

Featured photo via PublicDomainReview: Photographs of Palestinian life.

Leave a Reply