Let’s kick off with the good news: In the last few months people have started important conversations about the climate crisis. Some have even taken it to the next level and started walking the talk by making changes to their lifestyle to lower the damaging impact on our common home. Ranging from fast fashion and animal protein diets to plastic waste, cars and frequent flying, the taming of our over-consumption is finally beginning to make some waves.

It’s this search for solutions to curbing our carbon emissions that has put aviation in the spotlight. Why? Maybe because aviation is “one of the most energy and carbon intensive forms of transport, whether measured per passenger km or per hour travelling“; the most effective way to boost your carbon footprint, and the fastest growing source of greenhouse gases globally. Or maybe because it’s difficult to decarbonise this particular sector of the economy.

We can replace meat with plant protein, coal with solar and wind, diesel cars with their electric counterparts, but no, there aren’t many cleaner alternatives to that flight from New York to Paris. There are no electric planes yet, although, it’s true, Bertrand Piccard did finish his experimental flight around the world in a solar airplane.

Another hurdle is time. The latest data shows steep rises in CO2 for the seventh year, bringing the threshold of 450ppm (atmospheric CO2 concentration ppm) closer sooner than anticipated. And this June, Greenland was 40 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than normal, the ice sheet melting unusually fast. But there’s no guarantee any project aiming to decarbonise aviation will evolve fast enough to keep us up there, in the air, but without the huge carbon footprint. Carbon emissions must decrease rapidly if we are to meet the international climate targets and avoid the catastrophic effects of climate breakdown.

According to this article from Time (2016), biofuels are predicted to only make up 2.5% of aviation fuel for flights using U.K. airports by 2050. Other small steps like “single-engine taxiing and the use of lighter materials” (cutting around 1-2% of emissions each year) don’t seem to impress most climate scientists. Or the fast melting polar ice caps. That’s why, when it comes to aviation, in order to meet the carbon reduction targets along the other sectors of the economy, the only alternative is to fly less, or to stop flying altogether.

Further in-depth reading: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report on Aviation and The Global Atmosphere.

Crunching some numbers: The Aviation Environment Federation (AEF) published on their website some key aviation and climate change facts which are quite sobering. They focus mainly on the UK, where the share of emissions taken up by aviation is predicted to grow from around 6% to 25% by 2050. Heathrow international airport scheduled more passenger flights than any other airport globally, and just revealed its expansion plans for a third runway. All this while the number of flights using British skies on one day reached an all-time high of 9,000 in May 2019, exceeding the previous record of 8,854 set on 25 May 2018. That’s more than six flights per minute.

Interesting numbers: Only a small proportion (around 5% according to Time) of the world’s population account for the 2.1 billion passenger trips made annually (some 3900 billion passenger kms per year). But climate breakdown affects everyone – “particularly those from poorer communities in the global south, who are significantly less likely to ever set foot on a plane.”

“Air traffic currently accounts for about 3% of global emissions, which is three times more than the total emissions of a country like France. Traffic is growing by 4% per year and is projected to double by 2030. This is in complete contradiction with the objectives of the Paris agreement, which will require halving current greenhouse gas emissions by around 2030. With the growth projected, by 2050 the aviation sector alone could consume a quarter of the carbon budget for the 1.5°C target, i.e., the cumulative emissions from all sources that cannot be exceeded to limit global warming to this target.” — Anglaret, Wymant, and Jean (2019)

No Fly Climate Sci

So, given the above-mentioned facts, data, and predictions, it comes as no surprise that the No Fly Climate Sci website was created by Earth scientist Dr. Peter Kalmus as the main hub for a group of scientists, academics, and members of the public pledging to fly less or stop flying altogether. So far there are “60 Earth scientists and 140 other academics, and counting.”

But why? As the changing climate “poses a clear, present, and dire danger for humanity”, they believe that it’s important to align their daily life choices with that reality, and also because, in case we forgot, “actions speak louder than words.”

Why the focus on academics? “Academics are expected to attend conferences, workshops, and meetings. Many academics, including Earth scientists, have large climate footprints dominated by flying. Meanwhile, colleges and universities ostensibly exist to make a better future, especially for young people.” And they want their institutions to live up to that promise. But the group also hopes to increase awareness of the climate impact of frequent flying outside of the scientific community. Although flying currently accounts for less than 10% of the global climate impact, it often “dominates the emission profiles of the globally privileged few who can afford it.”

The no-fly movement resonates with the divestment movement — urging universities (among other institutions) to stop investing their money in fossil fuel companies. Just as the divestment activists, the academics in this group try to make their academic institutions realize that they have a responsibility “to be role models in an age of obvious global warming, and therefore to adopt policies and strategies for flying less.”

Care to sign? There is a petition calling upon universities and professional associations to greatly reduce flying. FlyingLess is the Twitter account attached to the petition, also sharing useful information on the topic.

Might come in handy: Here’s how this professor of Sustainability Science plans to reduce flying at Lund University.

Shaming individuals? Nope, those behind the No Fly Climate Sci believe that shaming is counterproductive, but that hasn’t stopped others from doing it. Productively. In Sweden, for instance, where the anti-flying movement is on the rise, “flight shame” and “train brag” have been added to the vocabulary. Two mums even persuaded more than 10,000 people to commit to not taking any flights in 2019 with their campaign No-fly 2019 (Flygfritt 2019). The numbers are expected to go much higher next year.

Politico considers that there’s already a “popular revolt against flying”, which “has gone from glamorous to scandalous”, while “the industry is scrambling to prop up its fading popularity.” And New York Times reporter Andy Newman calculated that his family vacation flights “melted 90 square feet of Arctic summer sea ice” during an investigation into personal responsibility and climate change you can read here.

Do you want to measure your flying emissions? Check out this online carbon calculator.

Useful ideas pushing for change

In its Green Travel section, The Guardian recently published a story on the growing numbers of travelers abandoning air travel to, well, “help save the planet”. It also mentions an interesting solution proposed by Siân Berry (co-leader of the Green party in the UK) who has called on people to take no more than one flight a year and suggested a tax should be imposed on further journeys.

BTW, did you know? There is no tax on kerosene. The Convention on International Civil Aviation (ICAO) (Chicago 1944) exempts air fuels already loaded onto an aircraft on landing from import taxes. More here.

Would you sign this? An initiative asking for ending the aviation fuel tax exemption in Europe.

Another good idea comes from Climate Perks (a project started by 10:10) which found that 50% of people are ready to reduce the amount they fly in response to climate change – but only 3% of us do. The key barrier? Our old friend: time. That’s why they came up with a solution that enables climate-conscious employers to offer paid journey days to empower staff to choose low-carbon holiday travel — by train, coach or boat instead of flying — and act on their values. These companies already joined the scheme. See how it works. In exchange, employers receive Climate Perks accreditation in recognition of their climate leadership. As they put it rather bluntly: “Don’t just get ahead of the curve, help bend it in the right direction.”

You can register your interest here, and join the Climate Perks pilot for take off (!) in 2019.

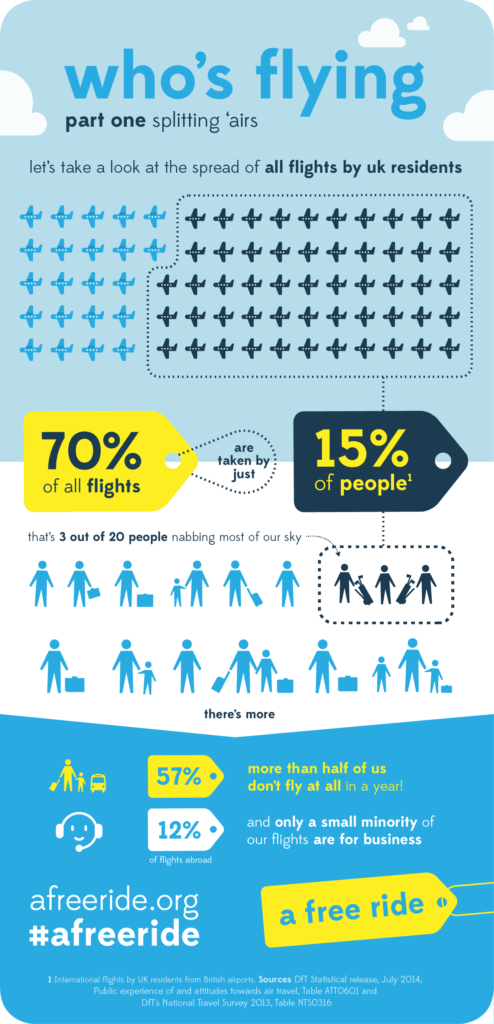

In the UK, New Economics Foundation think tank and A Free Ride campaign propose the Frequent Flyer Levy, because there’s “no way should everyone pay the same for a problem that hits the poorest and the richest cause.” They campaign for a fairer, greener tax on air travel: one tax free ride every year, with a rising levy on each flight after that.

“Most of us only take one or two flights each year at most, while a tiny handful are taking dozens of flights. Frequent fliers are causing untold environmental damage – and being rewarded for it with generous tax breaks which all of us pay for. As a result, Britain’s skies are already some of the busiest in the world. Yet the aviation industry wants to double the number of planes up there, and are demanding a new runway so they can do so.” — A Free Ride website

Find out more about tax justice, environmental justice and that “first class problem” here.

No-plane people and their slow-travel stories

The Twitter hashtag #FlightFree2019 created quite a buzz and it was partially inspired by the dozens of individual stories on No Fly Climate Sci. Yes, it’s a bit like Veganuary, but instead of meat and dairy, you give up flying for a year. And just as those enjoying their vegan January so much that they decide to go vegan all year round, many people who don’t fly for one year, decide to adopt no-flying full-time. Like this physics professor from Auckland who refused to get into a plane for one year (2018), choosing trains, buses and electric vehicles instead. He reduced his emissions down to about 2 tonnes from 19 tonnes of carbon dioxide — his year’s worth of travel emitted in 2017. His one year experiment was so good for him that he decided to just stop flying. No, he doesn’t miss it.

Climate activist GretaThunberg made her epic European trip in April 2019 by train. She hasn’t flown since 2015. While Climate Physicist David Romps recently took a three-day trip across the country by train. Here he explains why a train instead of the plane. Climate Scientist Peter Kalmus (the guy behind No Fly Climate Sci) is “a pragmatic idealist” in Katharine Hayhoe’s words. “He’s a scientist, so he doesn’t minimize the nature of our predicament. Yet he runs headlong towards that challenge with a joy and an infectious enthusiasm that buoys the spirit.”

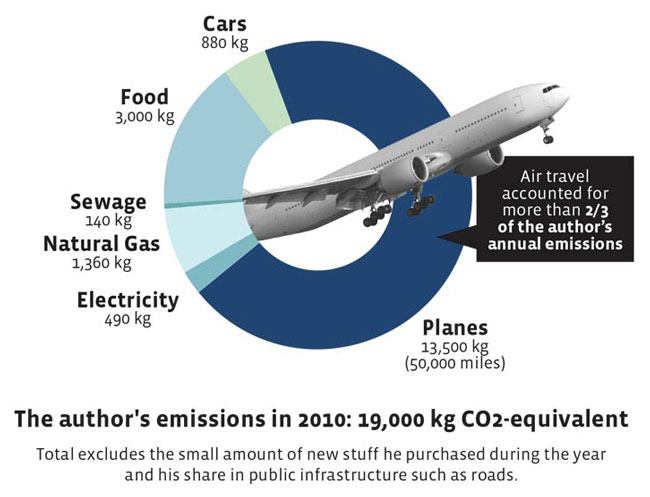

Kalmus slashed 90% of all his carbon emissions. When he started dissecting his carbon output, he realised the fastest way to lower his emissions was to cut the most guilty activity. Guess what, flying easily topped his list. As a scientist, he was frequently flying to conferences home and abroad, and those particular trips were the ones that pushed his flying score high enough to make him reconsider his traveling habits. He hasn’t flown since 2012. In the meantime he wrote Being the Change: Live Well and Spark a Climate Revolution (2017), an equally fascinating and inspiring book, breaking down into easy-to-digest chunks his journey to a low-carbon lifestyle. He talks about the challenges, the victories, and how the changes he implemented in his life made it a better life.

Further reading: Here’s an article Kalmus wrote for Yes! magazine in 2016. The graphs should help you better visualize the impact each form of transport and other carbon sources had in his life. If you want to go even deeper, do read his book.

“Hour for hour, there’s no better way to warm the planet than to fly in a plane. If you fly coach from Los Angeles to Paris and back, you’ve just emitted 3 tons of CO2 into the atmosphere, 10 times what an average Kenyan emits in an entire year. Flying first class doubles these numbers.

However, the total climate impact of planes is likely two to three times greater than the impact from the CO2 emissions alone. This is because planes emit mono-nitrogen oxides into the upper troposphere, form contrails, and seed cirrus clouds with aerosols from fuel combustion. These three effects enhance warming in the short term.” — Peter Kalmus

Further reading: And while we all wait “for the panacea of low-carbon technologies to become the norm”, have a look at another enlightening blog post. Hypocrites in the air was written by Kevin Anderson, professor of climate and energy and deputy director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research. His blog is available in PDF format and is now a chapter in the book Beyond Flying. Don’t miss the part on iteration, adaptive capacity and indulgences – how to avoid carbon lock-in.

More inspiring reads: On averting cognitive dissonance and the to fly or not to fly dilemma.

“By buying a plane ticket we are sending a very clear market signal: build more planes please, and expand airports while you are at it. What this does is lock the future into a high-carbon aviation infrastructure which is already operating at its maximum conceivable level of efficiency – that is, the jet engine isn’t likely to be getting any ‘cleaner’ any time soon, and so will continue consuming fossil fuels and emitting carbon dioxide at the same rates for as long as the infrastructure created to support it allows. On the other hand, train efficiency has a lot of potential to improve, and so travelling by train is sending a signal to the industry to make these improvements faster. Even better, trains can run on electricity which can – and increasingly will – be low-carbon.” — Anna Pigott (Postdoctoral researcher in Environmental Humanities)

What about offsetting?

For most of the people adhering to no flying, offsetting is not a solution. The No Fly Climate Sci community consider many carbon offset programs as mere greenwashing, “public relations gestures that may do more harm than good”, sometimes “worse than doing nothing”. In their opinion offsetting is “without scientific legitimacy, is dangerously misleading and almost certainly contributes to a net increase in the absolute rate of global emissions growth.”

Further reading: Find out more about their response to purchasing carbon offsets here.

Did you know? Half of the world’s biggest airlines don’t even offer carbon offsetting.

System change, not climate change

What’s even more interesting about the no-flying community is that most of these people didn’t stop flying just to reduce their carbon footprint in a race against the clock, or to feel less guilty about their consumption habits. They do something equally important: they experiment with a zero-carbon lifestyle, a lifestyle we may all have to adopt sooner or later, forced by circumstances if not by our own will. These no-flying-flying-less people continue to have successful and satisfying lives and careers. Some regard their move to a low-carbon lifestyle as an upgrade to their lives, and we all can catch a glimpse of a post-carbon future by reading their detailed stories meant to help change the culture in a society that still rewards frequent flying. It should give us all some food for thought, while pushing for systemic change with all the tools at hand.

“It’s a tough pill to swallow, but when you look at the issues around climate change, then the sacrifice all of a sudden becomes small.” — Lorna Greenwood (Environmental Activist) on giving up flying

It’s true that in most Western countries, a big part of the population takes flying for granted. It gives us a sense of freedom (justified up to a point), we feel that somehow we’ve earned the privilege of flying once available only to the rich and famous. We fear we’re missing out on those adventures promised on the billboards paid by air travel companies, and too often it is cheaper to fly (no fuel duty or VAT on tickets!) than to take a train. But it’s wrong to measure everything against a price tag, especially when the true cost is hard to measure in money (maybe because good planets are priceless).

By the way: There are some exciting new rail links across Europe. Apparently, these new services are helping travelers swap plane for train. National Geographic made a selection of thematic unforgettable rail journeys through Japan, and via Lonely Planet we discover that, surprise surprise, some train trips are cheaper and faster than flying.

At least the pre-boarding experience is changing

In the meantime, airports brag about their reusable coffee cup trials, their massive indoor jungles, and plastic-free flights, while the elephant in the airport is still successfully avoided.

But if a busy climate scientist and teenage activist manage to stop flying while still traveling and enjoying life, it sure is doable, right? Whatever you decide, do keep in mind that there’s more attached to the cheap price tag than meets the eye. No flying (or significantly reducing on your flying) is one of the most impactful behavior changes frequent flyers can take to cut carbon. So, what shall it be, are you gonna take a stand against carbon? Are you gonna fly less or stop flying?

~~~~

If you know anyone who stopped flying or is flying less, we’d like to hear their story of change. What about your community? Are they talking about this? Thank you!

Featured image via Shutterstock

Leave a Reply