“We never know the worth of water ’til the well is dry” – Thomas Fuller

What is low-impact water supply?

Over 70% of the Earth’s surface is covered with water. From space, we’re the Blue Planet. However, only 2.5% of this is fresh water, and two thirds of that is locked up in glaciers and ice caps.

The remaining third (c. 0.8% of all water) is distributed between lakes, wetlands, groundwater, rivers, soil moisture and atmospheric water. That’s too precious to be throwing away to pollution, habitat encroachment and climate change pressures.

Water supply is something that we take completely for granted on these wet islands off the west coast of Europe. Most of our tap water is pumped from groundwater, rivers or lakes and is filtered and sterilised to remove contaminants (mostly from sewage and agriculture) and sometimes medicated with fluoride (causing great debate as to its benefits and drawbacks).

Then, it’s pumped and stored for delivery to our homes. This process is carried out daily by local authorities across the UK, and yet we seldom give it much thought.

Our home planet is a watery, blue one.

A more ecologically sustainable water supply would be one that starts with clean water, so avoiding additional chemicals for sterilisation or medication, and relying only on gravity to deliver the water to our homes.

However, the management of our municipal water supplies and the health of the wider catchment area, the landscape on which our rain falls and through which our water flows, is beyond the direct control of most of us. Thus later in this topic intro are more modest contributions that we can make towards catchment protection and diversification of our own private water supplies.

What are the benefits of low-impact water supply?

Availability of clean water is one of the essential requirements for a healthy life. We use it in our home for drinking, cooking and cleaning; in our farms for irrigation and for livestock; in our industry for cooling, cleaning and production processes. It’s the lifeblood of our countryside and all of the habitats we know and love.

We too are mainly water, to the tune of about 60%. This simple molecule H2O – two hydrogen atoms for each oxygen atom – provides us with the basis of all life on Earth. Everything that lives and breathes relies upon water for its existence.

The bed of a stream seen through crystal clear water; clean water is essential for life.

In recent years and decades we’ve seen water shortages due to droughts, deterioration of water storage within our catchments, contamination and deterioration of the water quality in our groundwaters, rivers and lakes.

Paradoxically, storms also bring water shortages from time to time because of our dependence on electricity for pumping water to our municipal treatment systems and/or our homes.

There are many varied benefits from moving towards a lower-impact water supply. The benefit of diversifying our water supply is that we can build greater resilience into our lifestyles; the benefit of adopting water conservation measures (and diversification of supply) is that we reduce the total demand for pumping and chemicals at the municipal level; the benefit of protecting our local catchments from pollution and hydrological extremes is that we can all have cleaner, healthier water to drink; and the benefit of reducing our water footprint is greater health and wellbeing of those who live far removed from us and yet are affected by our lifestyles and purchasing habits.

Wetlands and woodlands filter and store water within our river catchments. We need these areas to protect against flooding and droughts.

What can I do?

There is plenty that we can do to help protect clean water, diversify our supplies, conserve water and to reduce our global water footprint.

When rain falls on the land, water is filtered and stored in the soil, particularly healthy humus-rich soils and in woodlands and wetlands. To protect the quality and reliability of our water supplies and habitats we can support organisations that encourage tree planting in our uplands, preservation of our wetlands and promotion of agricultural practices that encourage good soil health.

Even something as straightforward as composting in our back gardens builds humic material in our soils and helps to provide greater water storage in our soils.

On an individual house basis, we can create rain-gardens or mini SUDS units to contain heavy rainfall from our roof surfaces or driveways and gradually reintroduce this water back into the ground via percolation from the system base. This reduces the pressure on mains drainage networks and protects rivers and streams from hydraulic shock loading, flood/drought cycles and pollution.

If we farm or manage land, then we can introduce woodlands, hedgerows, wetlands or ponds within the catchment to contain heavy rainfall and release it slowly back into the wider groundwater or river system, filtering it as it goes. We can compost and practice regenerative agriculture to build our soil humus content and thus provide additional catchment storage and water filtration.

Example of a small rain garden / SUDS system.(source: Susdrain)

Get involved in a local Rivers Trust to ensure that your local catchment area is being cared for, to keep your drinking water clean and healthy. It’s also important to ensure that your own sewage system is working well so that you’re protecting the underlying groundwater.

When it comes to our own water supply, we can explore ways to diversify our sources to have greater resilience in an uncertain future. One of the principles of permaculture reads: “each important function is supported by many elements”. Well, access to clean water is certainly one of the mort important ‘functions’ in our homes. It often goes unnoticed because, like clean air to breathe, we take it so completely for granted.

However, without a ready supply of electricity to filter out contaminants from sewage and agriculture, our water supplies can become unsafe to drink. Without electricity to pump it, our taps quickly run dry. This ‘important function’ suddenly becomes horribly noticeable only by its absence.

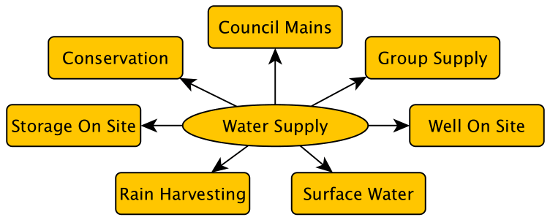

The image below shows a variety of water supply sources; conventional and alternative. By diversifying our water supply we can build resilience into the design of our homes and lifestyles. Council mains supply, group scheme supply and private wells on site are all relatively common water sources. These all typically require pumping to deliver water to our taps, and often require extensive filtration and sterilisation in order to remove contaminants.

Diversification of water supply sources. (Source: FH Wetland Systems)

Although surface water abstraction from rivers or lakes is a relatively common method of water supply on a municipal scale, it’s much less common for individual homes. If you’re fortunate enough to live in an area with a clean river or stream running close to the house, this method may be ideal, but you can by no means take for granted that the supply will be clean or safe to drink.

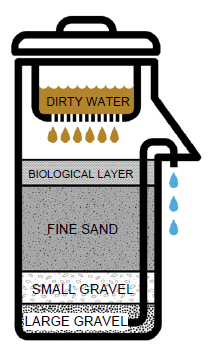

Used with a biosand filter however, it may be possible to safely provide your primary supply or even a backup in the event of an interruption to your existing source. Ideally, set up your system to run using gravity rather than needing to be pumped.

Rain harvesting is another water supply method that’s growing in popularity. The three main elements to any rain harvesting system are the catchment (your roof), supply (the gutter system) and storage (tank or chamber). If these are all carefully designed you can safely capture and use harvested rain water to augment or replace your mains supply. Filtration may be required if you want to use rainwater as a drinking water source.

Note that rainwater hasn’t had the benefit of contact with the earth, filtering through the soil and picking up minerals from the bedrock, so it may not be as healthy a source of drinking water for ongoing use – research this further if you want to use it as your only supply (see here and here).

Basic diagram of a biosand filter.

If you have clean water below ground or in a local river or stream, but not the falls to obtain it by gravity, there are a number of low-impact pumping options. One is a wind pump, which can be used for groundwater or surface water access. Another is a ram pump, for use with rivers or streams where the flowing water provides the energy to pump a small volume of water to a header tank.

I’ve not even considered bottled water as a water source, although many people clearly do. Imported bottled water has a carbon footprint of about 300 times that of tap water, and c.14 billion recyclable plastic bottles end up in landfill every year in the UK, so bottled water won’t win the low-impact prize.

Better to keep our landscape and produce healthy drinking water than to stock up on bottles which are often simply bottled tap water anyway, or at worst sourced from water-stressed regions which need to keep their groundwater in the ground, rather than exporting it at great profit to just one private company.

Water sources that don’t need electricity to pump: hand-drawn groundwater abstraction; gravity-fed or hand-drawn surface water abstraction; rain.

Storage on-site is listed in the water sources image above, in order to identify this as a possible backup for use during power shortages. Storage may best be achieved in an additional cistern if you experience regular short-term power supply interruptions. Alternatively, having an outside tank or garden pond to act as a reservoir may provide useful storage for occasional use.

A few years ago we had a big freeze, and our household mains supply was down for about a week. At the time we turned to the four large water tanks used for storing rain water for our polytunnel. These thawed faster than the council mains supply and we were able to boil the water for drinking and washing – and were very glad to have this diversity of water sources.

Conservation of water is another heading that isn’t strictly a water supply source, and yet in many respects if we can be frugal with our water use, we can reduce our ecological footprint by cutting back on council electricity use for pumping and abstraction from our local waterways.

There are many simple ways to conserve water, such as using low-water-use taps and washing machines, summer watering of the garden with washing-up water, turning off the tap when brushing your teeth etc. We can install low-flush toilets or waterless urinals to further reduce our water consumption, or for source separation of urine to use as a fertiliser rather than adding to the nutrient-loading on our local municipal treatment system.

Grey water recycling is another option, but personally I’m a fan of using rainwater in preference to filtered grey water because it typically involves less energy, and we already have an abundance of rain.

While water (and electricity) is so abundant it can be difficult to see the justification for water conservation – however, as our weather patterns become more extreme, some people are being faced with lugging water from central depots – even if only on an occasional basis. Conservation of water supplies suddenly becomes important when each litre is carried by hand in a Jerrycan.

Two types of pump that don’t need electricity: wind pump and hydraulic ram pump.

However, in general terms domestic use accounts for a relatively small amount of our water footprint – which is the amount of water used to produce the goods and services that we buy. This extends well beyond our shores. A quarter of the world’s agricultural land is in areas that are already water-stressed, and these areas are spreading as climate change takes its toll.

In Europe, some 40% of our water footprint is generated abroad in the form of imports, often from very water-stressed regions. When we buy almonds, avocados, pistachios, wine and cotton we often put additional pressure on areas that are already suffering from drought conditions. Beef raised in water-stressed areas is worse again, so if buying beef, be sure to buy only local beef, where we have the rainfall to meet the demand.

In light of this, be sure to consider water-stressed areas in your shopping habits and endeavour to stop buying water-intensive crops or products from such regions of the globe. This is another good reason to buy local and grow our own food!

Leave a Reply