The stimulation of modern life, philosopher Georg Simmel complained in 1903, wears down the senses, leaving us dull, indifferent and unable to focus on what really matters In the 1950s, writer William Whyte lamented in Life magazine that ‘billboards, neon signs,’ and obnoxious advertising were converting the American landscape into one long roadside distraction. ‘A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention’, economist Herb Simon warned in 1971.

The sense that external forces seek to seize our attention isn’t new – but it feels particularly acute today. Billboards, shop windows, addictive digital games, an endless news cycle and commercial appeals tantalise us from all directions. We contend with the myriad distractions flowing through the pocket-size screens we carry with us everywhere. By various estimates, a typical smartphone owner checks a device 150 times per day – every six minutes – and touches, swipes, or taps it more than 2,500 times.

It can feel like everyone we’ve ever known, every business or cause, wants – demands – to claim our attention. Polyconsciousness is what one researcher termed the resulting state of mind that divides attention between the physical world and the one our devices connect us to, undermining here-and-now interactions with actual people and things around us.

“Over the coming century, the most vital human resource in need of conservation and protection is likely to be our own consciousness and mental space.” — Tim Wu

It’s true, as many have observed, that human distractibility – the way we’re instinctively drawn to the proverbial bright and shiny objects – is hardwired, a function of evolution.

But it’s also true that, more than any other creature, humans can outmanoeuvre our own base instincts. That’s why it’s no coincidence that peak distraction has coincided for instance with a vogue for meditation and mindfulness: We know we’re distracted and we yearn to see the world more clearly. We also know we can learn to direct our attention where we wish to.

What we do with our attention, in short, is at the heart of what makes us human.

That is exactly what the art of noticing will help you find out. It is comprised of exercises and provocations meant to help you counter distraction by inspiring you to make the small yet enjoyable effort to rediscover your sense of creativity and wonder.

1. Look slowly

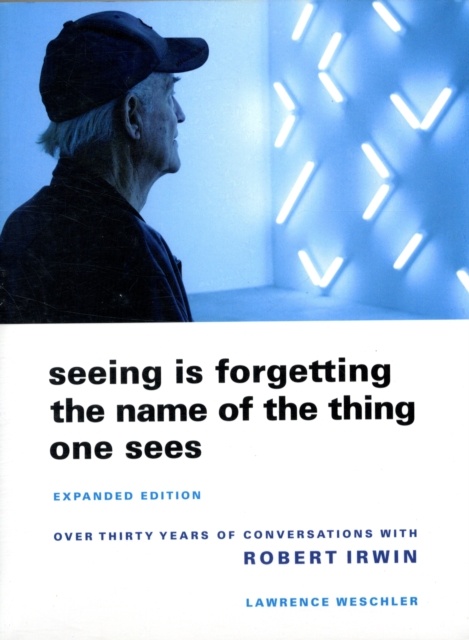

The artist Robert Irwin is surely the patron saint of noticing. As detailed in Lawrence Weschler’s book Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, Irwin’s work focuses on the experience and context of seeing, rather than on producing art objects – ‘allowing people to perceive their perceptions’, as Weschler put it.

Irwin started out as a painter but spent lots of time staring at his canvas, not painting anything at all. He obsessed over the details of the gallery spaces where his work was displayed – the angles, the floorboards, the light. He once spent eight months in Spain, producing nothing.

‘I found a certain strength in sustaining over a period of time my attention on a single point’, Irwin told Weschler. ‘After a while, it’s like you peel back the layers of that issue and are able to get to a much deeper reasoning of how and in what way this thing makes sense’. Gradually he transitioned to making work such as acrylic discs that treated light as their medium. He made ‘site-dependent’ work, installations that transformed the way we see a particular space.

It’s possible to borrow Irwin’s practise and apply it on a more practical scale. Slow Art Day offers an example. This is an annual event held at multiple locations across the United States; participants are invited to meet at a museum, SlowArtDay.com explains, and ‘look at five works of art for 10 minutes each, and then meet together over lunch to talk about their experience’.

You don’t have to wait for the next Slow Art Day to try this. It’s fun to spend such time with a work of art, but you can also look at five products at your local department store for ten minutes each.

Simple as this sounds, the art of noticing is quietly radical. A study by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York concluded that its patrons spend a median seventeen seconds in front of any given painting. Start with Slow Art Day’s ten minute benchmark. You’ll get a glimpse of what drives Irwin’s remarkable process: You’ll see details you missed, you’ll draw new connections and you’ll reconsider first impressions.

2. Look like a child

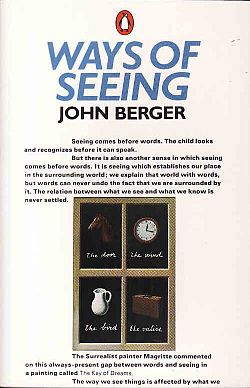

John Berger, in his famous Ways of Seeing documentary series and book, relentlessly critiqued visual culture, teasing out secret histories and exposing stealthy biases. It was (and remains) a sophisticated and nuanced take on perception.

But Berger also pointed out that often the most honest, blunt and no-nonsense observers are not highfalutin culture critics. They are children. Not yet having absorbed any particular sense of what is of acceptable cultural interest and what isn’t, children see novelty and wonder in the familiar. They notice what we’ve long since learned to ignore.

‘The child sees everything in a state of newness; he is always drunk’, Baudelaire wrote. ‘Nothing more resembles what we call inspiration than the delight with which a small child absorbs form and colour’; this is the ‘genius of childhood – a genius for which no aspect of life has become stale’.

The artist Yolanda Dominguez made a short film that I suspect Berger would have loved. She asked children to offer their perspective on high-fashion and luxury-brand imagery. In Niños vs. Moda (‘Children vs. Fashion’), a group of eight-year-olds are presented with fashion ads and asked to describe what they see. ‘She seems … scared’, a boy offers in reaction to one image. ‘She needs a first-aid kit to get healed’, a girl says. ‘She feels alone’, adds another boy. ‘And she’s hungry’.

Sad as that all sounds, it’s also revelatory. Children are blunt and curious and they are effortlessly imaginative and insightful.

We may never be able to recapture exactly the feeling of looking at the world before we’d spent so much time looking at the world. But next time you are confronted with some scene or situation that feels numbingly familiar, stop and ask: what would a child see here?

“Expand your attention to include everything that you can possibly hear, without judgement. The ear hears. The brain listens.” — Pauline Oliveros

3. Listen Deeply

The composer Pauline Oliveros was known, among other things, for a practise she called deep listening. This evolved in part from her experience performing with a couple of other musicians in an abandoned cistern in the state of Washington, three metres underground. The group shared a weakness for bad puns and titled a 1989 CD of their recordings in the space Deep Listening.

But the extraordinary reverb in the cistern really had forced the musicians to listen with deep and extraordinary care to their environment. Thus the performances (there was no audience) prompted them to think in new ways about the relationships between the sonic and the spatial. This led to the Deep Listening Band, Deep Listening workshops and ‘retreats’, and eventually the Deep Listening Institute. Oliveros later explained that the practise developed into something that ‘explores the difference between hearing and listening’.

Hearing is a physical process involving sound waves and the body. We know about it because it is easy to study; listening, the interpretation of those sound waves, is harder to quantify.

‘To hear is the physical means that enables perception’, Oliveros continued. ‘To listen is to give attention to what is perceived, both acoustically and psychologically’.

Oliveros’s version of listening encompasses remembered sounds, sounds heard in dreams, even imagined or invented sounds. Elsewhere she referred to auralization (a term borrowed from architectural acoustics) as a kind of sonic corollary to the visual spin we tend to put on imagination. ‘Listening is a lifetime practise that depends on accumulated experiences with sound’, she asserted, one that encompasses ‘the whole space-time continuum of sounds’.

Well before arriving at the term deep listening, Oliveros had experimented with many of these ideas and notably produced a short but influential 1974 text called Sonic Meditations, offering various sets of rather poetic instructions:

Take a walk at night.

Walk so silently that the bottom of your feet become ears.

Most of the highly inventive prompts also involve making sounds, particularly in groups, consistent with her belief that musicality shouldn’t be restricted to musicians. For example, ‘Choose a word. Listen to it mentally. Slowly and gradually begin to voice this word by allowing each tiny part of it to sound extremely prolonged. Repeat for a long time’.

You can piece together and modify some of Oliveros’s suggestions to explore deep listening without worrying about compositional goals. Here is one approach to experimenting with the kind of expansive listening that she advocated, borrowing from a few sources, but most notably a ‘meditation’ that was part of a 2011 Deep Listening Intensive in Seattle. Think of this as a means of exploring your aural identity: in any space you wish, ‘listen to all possible sounds’. When one sound grabs your attention, dwell on it. Does it end? Think about what it reminds you of. Consider sounds from your past, from dreams, from nature, from music.

Now think of a sound that reminds you of childhood; see if you can find something reminiscent of that sound now. Dwell on what you find. Stop here or follow the instruction of that 2011 meditation for as long as you wish: ‘Return to listening to all sounds at once. Continue in this manner’.

This is an extract from the recently released The Art of Noticing by Rob Walker.

Re-published with the kind permission of the author.

Leave a Reply