In December of 1924, the heads of all the major lightbulb manufacturers across the world met in Geneva to concoct a sinister plan. Their talks outlined limits on how long all of their lightbulbs would last – the idea being that if their bulbs failed quickly, customers would have to buy more of their product.

Our Changing Climate series

This post is part of a new series created by ethical.net in partnership with Our Changing Climate, an environmental YouTube channel that explores the intersections of social, political, climatic, and food-based issues. Get early access and support this important research by becoming a Patreon.

In this video, we’re going to unpack this idea of purposefully creating inferior products to drive sales, a symptom of late-stage capitalism that has since been coined ‘planned obsolescence’.

And as we’ll see, this obsolescence can have drastic consequences for our wallets, waste streams, and even our climate.

What is planned obsolescence?

Corporations create obsolescence through two main avenues: planned obsolescence and perceived obsolescence. These practices make products seemingly or actually useless, in order to drive sales.

Planned obsolescence occurs when a company manufactures a device to fail before the end of its realistic lifespan. This usually means a weaker filament, plastic encasement, or a fragile glass screen that limits durability.

💡 The group of 1920s electricity companies known as the Phoebus cartel applied this principle to lightbulbs. The Phoebus cartel collectively halved their products’ lifespan, from 2,000 to 1,000 hours, so that consumers would have to buy twice the amount of lightbulbs than they did previously.

What is perceived obsolescence?

On the other side of obsolescence, there’s the more amorphous phenomenon of ‘perceived obsolescence’. Think of that new phone you bought, that new style of clothes you’ve been eyeing, or even this year’s new line of pickup trucks. All these are instances of perceived obsolescence.

When companies release a new line of products, their older products quickly become unfashionable or less desirable. In order to get you to keep buying their goods, corporations consistently market new lines to make it seem like that new gadget you bought just a year ago is an antique – even though, in most cases, the older product still works.

Perceived obsolescence is especially prevalent with cars, technology, and fashion, because these consumer goods have been transformed into status symbols. If you want to keep up appearances, you grab the newest model of iPhone. If you want to look good, you buy the latest style from that Instagram ad.

But how and why do planned and perceived obsolescence work on us?

How obsolescence happens

As we’ve just seen, modern obsolescence comes in various forms: from brittle parts that break easily, to glued-in batteries you can’t replace, to aesthetic upgrades that make the previous version unfashionable. And it seems that the master of all these methods is Apple.

It’s one of the top three phone producers in the world, as well as the most valuable company globally. In part, the tech giant’s market dominance was created by and now allows for Apple to employ an environmentally dangerous combination of perceived and planned obsolescence that leads to consumers buying a brand new iPhone every two or three years.

For the iPhone, it all starts with the battery. After about two to three years of peak performance, the iPhone battery begins to wear out. But if you want to change the battery, it’s not as simple as popping the back open and sliding in a replacement. Depending on the version of the iPhone, you’ll need special screwdrivers, adhesive removers, suction cups, and possibly even a soldering gun just to replace your rundown battery. 🚮

In an interview with the team at the popular DIY tech website iFixit, they call the iPhone battery a “premature death clock that they’re building [in as] a consumable designed to increase the number of iPhones Apple sells.”

Apple’s normalisation of the built-in battery, which, before the age of the iPhone, was rarely seen in cell phones, nudges customers into buying new to avoid struggling to replace the battery. And if you do want Apple to replace a battery, or fix some other damage to your device, you’ll have to cough up a lot of cash – at times, 50 to 70% of the phone’s original cost.

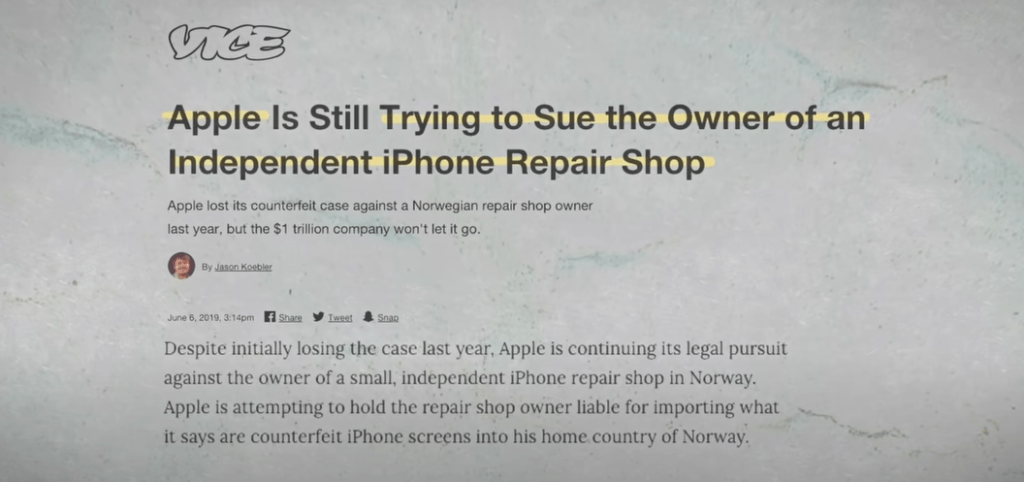

This is because you can’t just take your iPhone to any old repair shop. Only Apple stores and Apple-certified repair locations are allowed to fix iPhones. So, when the cost of repair is high and the newest model of iPhone has just been released, it’s difficult to not splurge on that new device. This is, yet again, another barrier against reusing your phone, reducing consumption, and ultimately minimising your environmental impact. ♻️

Finally, Apple’s warranty only covers your freshly purchased iPhone for one year, which is well before the two- to three-year range when Apple’s hardware typically begins to fail. The point here is this: none of these practices are necessary for the production or sale of Apple’s products.

👉 Apple intentionally chooses to build this waste into its product design and business plan, because these steps are necessary to make the company a tech giant and capitalist behemoth.

Indeed, Apple admits how long they expect their devices to last: seven years. After seven years, their products, in their words, “become obsolete.”

But wait, Charlie, isn’t seven years kind of a long time for a phone or computer to last? It may sound like a long time now, but prior to the advent of this iPhone paradigm, spending $1,000 on a product that would be obsolete in seven years at most would have felt completely unreasonable.

Many of us are so surrounded by planned and perceived obsolescence that we have been primed to think that owning a single device for seven years is actually a long time.

And even if their phones do last the full seven years, Apple creates perceived obsolescence by consistently marketing their phones through prisms of aesthetics, lifestyle, and status. Even that green bubble in iMessage seems to be telling us that other phones are somehow worse.

👉 So, at the end of the day, if Apple genuinely did want you to continue using your phone, then they would offer longer warranties or create more durable, easily repairable tech. But they don’t, because once you’ve captured the market like they have, obsolescence becomes pretty damn profitable.

Apple, however, is just one of many examples of obsolescence in capitalism. There’s Epson’s proprietary ink cartridges, barely modified new editions of school textbooks from McGraw Hill, and even Tesla seems primed to be next, with its reluctance to allow independent auto-repair shops to service their cars, a move remarkably similar to that of Apple.

Both planned and perceived obsolescence lead to that pile of perfectly operable phones in your desk drawer, as well as fuelling the 50 million metric tons of e-waste created each year. These corporate practices make our quest to embrace climate-aligned actions, such as reusing and reducing consumption, much harder.

In short, manufactured obsolescence fuels consumerism and environmental degradation in an already overconsuming world. So if it’s clearly a terrible scheme for our wallets, wellbeing, and the environment, how do we stop it? 👇

A new economic model

Luckily, there are a variety of short- and long-term solutions for getting rid of planned obsolescence.

On an individual level, simply taking the time to repair, take care of, and reuse your possessions is a great first step. But as we’ve just seen, companies have a vested interest in making that as hard as possible – both through the lack of durability of their products, and by influencing your mindset through advertising.

Which means that Right to Repair campaigns and court cases like these 👉 are essential to easing the unnecessary burden on the consumer.

But as we zoom out further, companies like Apple must be forced to change how they do business.

France already has laws against planned obsolescence, and companies like Fairphone show that it is possible to make a longer-lasting phone that is easy to repair. The battery on the Fairphone only takes about eight minutes to replace.

But ultimately, obsolescence is a symptom of late-stage capitalism. So if we want to create a world in which durable, sustainable products are the norm, we have to embrace a new mindset and build a new economic system that asks, at every stage in the process:

“Does it actively contribute to humans and nature thriving together as one integrated system on this planet? If yes, green light. If not, red light. Period.”

If all of this sounds hard or impossible, science tells us there can be no other way. Since the early eighties we’ve known that global temperatures will rise if left unchecked, and yet we’ve made very little progress since then. So, the world – and for that matter, our economy – needs to change. Eliminating planned obsolescence is just one step on the path to a more just, more sustainable economic system.

Leave a Reply