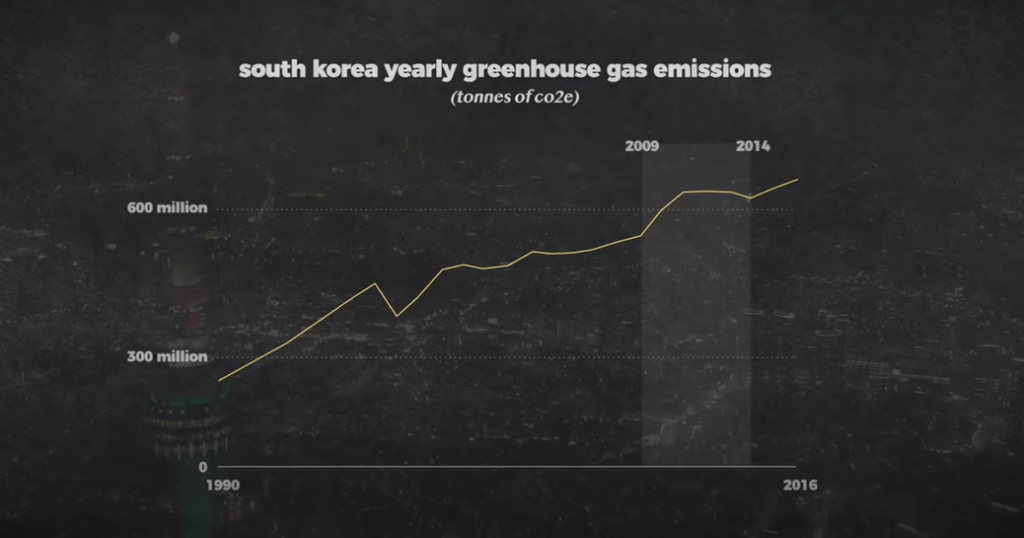

In 2009, South Korea did something remarkable. The country poured 2% of its GDP – some 38.1 billion US dollars – into environmental projects, hoping to create one million green jobs over the next five years. The goal was to spur growth in a slumping economy while simultaneously creating a low-carbon society.

In one sense, the plan worked.

Our Changing Climate series

This post is part of a new series created by ethical.net in partnership with Our Changing Climate, an environmental YouTube channel that explores the intersections of social, political, climatic, and food-based issues. Get early access and support this important research by becoming a Patreon.

South Korea’s economic system did eventually recover, but in a more important sense, the plan failed. From 2009 to 2014, Korea’s emissions rose 11.8%. So, despite massive investments in clean energy, railway expansion, and energy efficiency, South Korea’s emissions still climbed. 👇

What happened? Why didn’t South Korea’s green growth strategy work?

Today, we’ll answer that question and more in order to understand one of the insidious spectres that haunts the green energy revolution: consumption.

How consumption causes climate change

It’s December and the streets of New York City are filled with Christmas: stores, trees, lights, bags, packages, and trash.

Christmas in America is a sacred capitalist holiday wherein the average American explodes their average yearly emissions footprint by roughly 650kg of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO₂e), while spending a cumulative $2.6 billion on wrapping paper. 👀

Up until around 150 years ago, however, the holiday rarely saw a wrapped present in sight. But then unofficial holidays like Black Friday and department stores like Macy’s started to encourage shoppers to fill their carts with tech and trinkets, as a means of expressing care and love.

Now, Christmas shopping epitomises the consumer experience in the United States. It’s driven by a complex mix of personal desire, social pressures, status-signaling, stress, and propaganda that works, in many instances, not to increase personal well-being, but to pad the pocketbooks of corporations.

Advertisements on Instagram and billboards in Times Square bombard us with visions of what we could be if only we had that watch or phone, which locks us into a world where, in order to find happiness or comfort or political change, we need to buy… stuff.

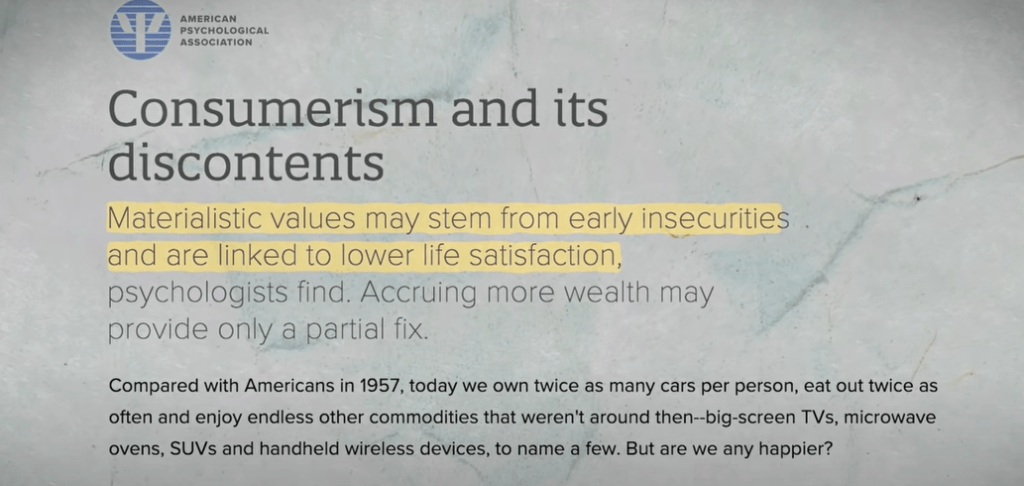

👉 But a range of studies have consistently found that once a person’s needs are met, extra consumption does not increase their well-being.

And buying new phones, clothes, and gadgets all have an environmental price tag. Despite the fact that 100 companies were found to be the root cause of 70% of global emissions, the reality is that the people using those companies’ products and burning their fuel are us.

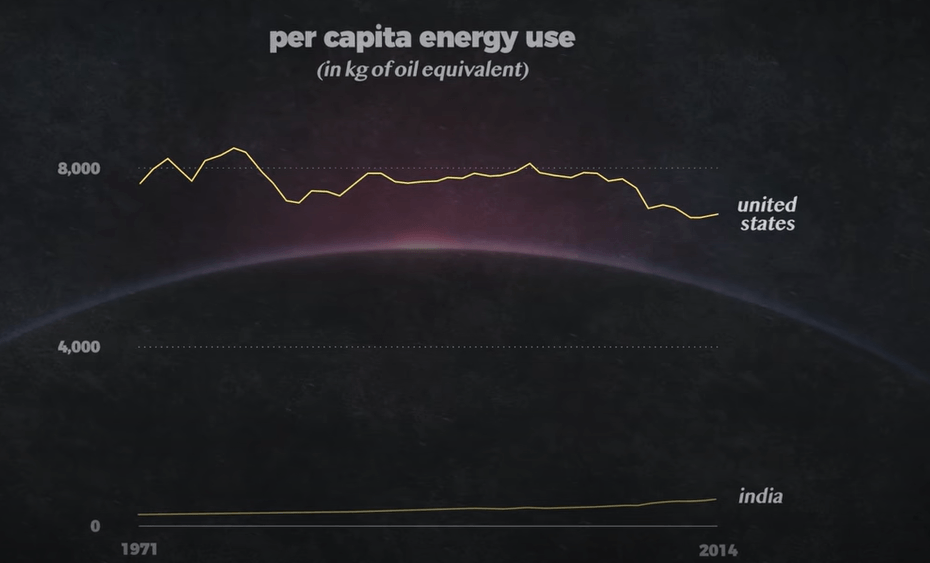

Or rather, I should say, primarily rich communities and countries. Because consumption levels are not equal across the world, the average American uses over 100 times the energy as someone from India.

And if everyone in the world were to live in the same way the average German does right now, global emissions would double. So as those in rich countries gorge on luxury items and the newest tech, they use energy and emit at much higher rates than countries in the majority world, which often are the ones feeling the brunt of climate disasters.

Why we can’t buy our way out of climate change

The blame for overconsumption should not and cannot be placed solely on individuals. Companies and corporations have a vested interest in making you buy more stuff, because if they don’t, they go bankrupt. Which is why they slap green labels onto their products and advertise everywhere.

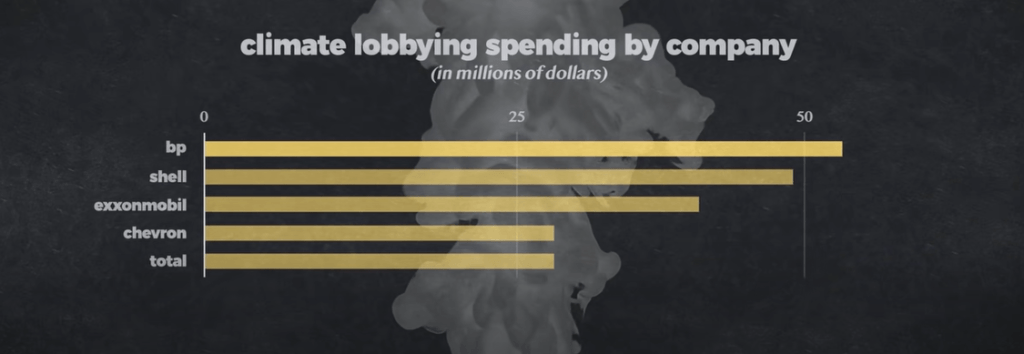

Indeed, the whole idea of a personal carbon footprint is a propaganda campaign created by the fossil fuel giant BP. 👣

The move allowed them to lock-in decades of fossil fuel use by turning attention away from their complicity in climate change, and instead blaming the individual for not living a low carbon lifestyle or not buying the right thing.

The natural conclusion, in a system riddled with ads and cultural norms imploring all your senses to buy more, is that your dollar is your vote. An idea which stands in stark contrast to the democratic ideal of one person, one vote. We are led to believe that growing the economy, which for the individual means buying more, whether it be supporting new green tech, or wearing sustainably-made clothing, is how we stop climate change.

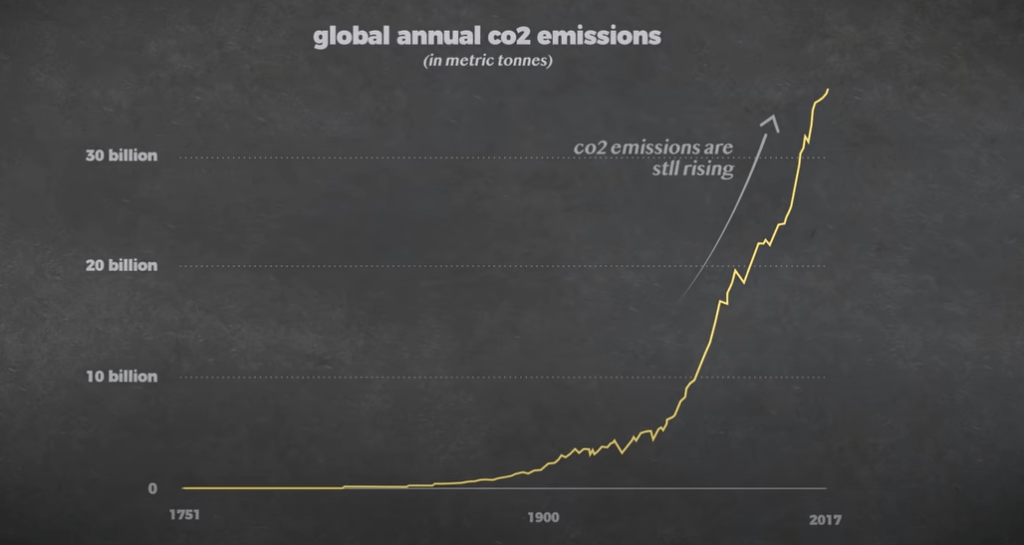

But the reality is that this capitalist growth model counteracts the work being done to decrease emissions. Over the last 40 years, global emissions have skyrocketed despite dramatic expansions of renewable and energy-efficiency technologies.

Yes, growth does lead to an expansion of new sustainable innovations, but it also leads to the expansion of fossil fuel-intensive industries.

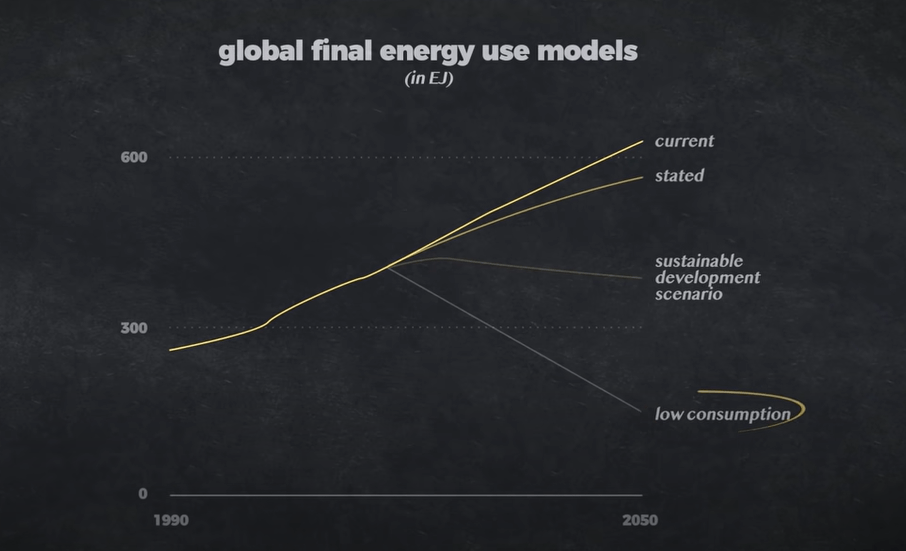

Just 1% growth in GDP leads to a 0.5 to 0.8% increase in carbon emissions. And if we continue to grow at 3% per year, by 2043 the global economy will be twice as large as it is now, which means energy consumption will be larger and the task of transitioning towards a zero-carbon world will be much harder.

So, something’s got to give. And that something is consumption in rich countries.

What options do we have?

The unfortunate reality is that expanding zero-carbon technologies to meet global energy demands, or what’s known as decoupling emissions from growth, will be an extremely difficult task. A task that South Korea attempted back in 2009 before running headfirst into the consequences of a growth-centred economy.

The reason South Korea’s emissions still rose 11.8% over five years is that their total energy consumption outpaced renewable installation and energy-efficiency projects. So the emissions they saved with green technology were nullified by their overall increase in consumption levels.

So then, what options do we have?

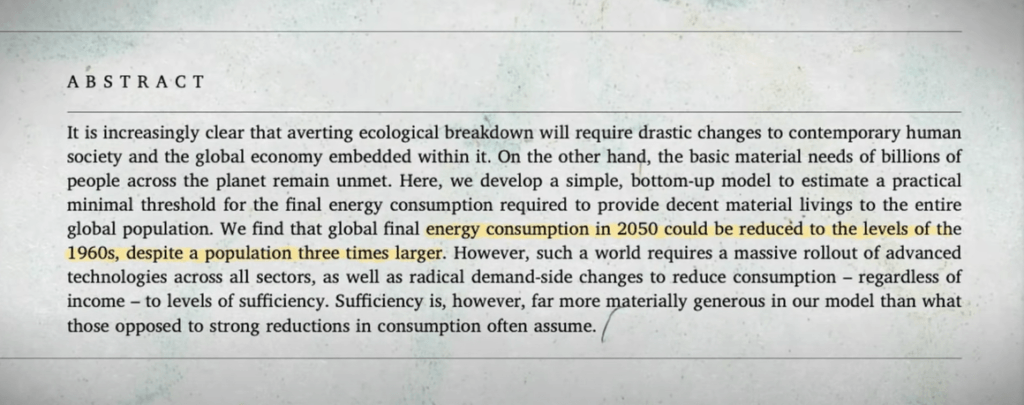

A recent study modelled that by 2050 the world could support the equivalent of three times the current global population – if global consumption levels drop 60% back down to 1960 levels. Most notably though, the paper claims that this is possible while still maintaining or even improving a decent lifestyle for all. And within their definition of a decent living, the researchers include laptops, comfortable climate control, access to robust transportation networks, and universal healthcare.

In order to achieve this world wherein everyone is able to enjoy a decent lifestyle while also avoiding a climate emergency, the researchers suggest a dual-pronged approach.

On the demand side, consumption levels must drop by as much as 95% in countries with today’s highest per-capita consumers. That means no more second houses or eating red meat every single day of the week.

👉 This must be simultaneously coupled with massive roll-outs of advanced technology in energy efficiency, renewable energy, and other sectors.

Together, the model predicts that these scenarios could allow the global population to live well in a zero-carbon world. And if all this sounds scary, Hope Jahren, author of The Story of More, compares this future lifestyle to that of someone living in Switzerland in the 1960s – which, to me, doesn’t sound that bad, especially considering that everyone in the world would be able to live the 1960s Swiss life. 👍

Towards degrowth

The key point here is that reducing emissions or what’s known as decoupling emissions from growth is not enough to quickly prevent the worst-case climate change scenario. Reducing consumption has to be integrated into our solutions toolkit if we are to quickly tackle the climate crisis before 2050.

But the burden of this task should not be laid upon the individual; it’s the job of governments and the very corporations who created the mess in the first place to facilitate this drop in consumption.

Imagine for a moment if, instead of lobbying for fuel subsidies and spending millions telling us to decrease our carbon footprint, BP was required to address its complicity in climate change by leaving fossil fuels in the ground and developing ✔️ renewable energy, ✔️ rapid public transportation, and ✔️ energy-efficiency technologies. I’d imagine the task of reducing our own consumption and emissions would probably be a lot easier.

Ultimately, degrowth is a path we need to take seriously if we are to tackle the climate emergency. While I can’t pretend to predict the far-reaching consequences that reducing growth would create, I do know one thing: the smaller our global needs, the easier the transition will be.

Leave a Reply