Tearing through the crowded streets of Philadelphia, an electric car and a gas-powered car sought to win a heated race. One that mimicked cars’ actual use: they had to stop at stop lights, wait for pedestrians to cross the street, and swerve in and out of the hundreds of horse-drawn buggies.

That’s right: horse-drawn buggies – because this race took place in 1908.

Our Changing Climate series

This post is part of a new series created by ethical.net in partnership with Our Changing Climate, an environmental YouTube channel that explores the intersections of social, political, climatic, and food-based issues. Get early access and support this important research by becoming a Patreon.

It was intended to settle once and for all which car was the superior urban vehicle. Although the gas-powered car was more powerful, the electric car was more versatile. And as the cars passed over the finish line, the defeat was stunning: the 1908 Studebaker electric car won by 10 minutes.

In 1908, the electric car was clearly the better form of transportation – so why don’t we drive them now?

Today, I’m going to answer that question by diving into the history of electric cars – and what I discovered may surprise you.

The race for electric (1870-1920)

In 1881, at the blistering pace of 9 mph, inventor Gustave Trouvé introduced the streets of Paris, and ultimately the world, to the quiet hum of the electric carriage. For the wealthy socialites of Paris, and their counterparts in New York, the horseless carriage was a must-have, and electric motors were the superior choice.

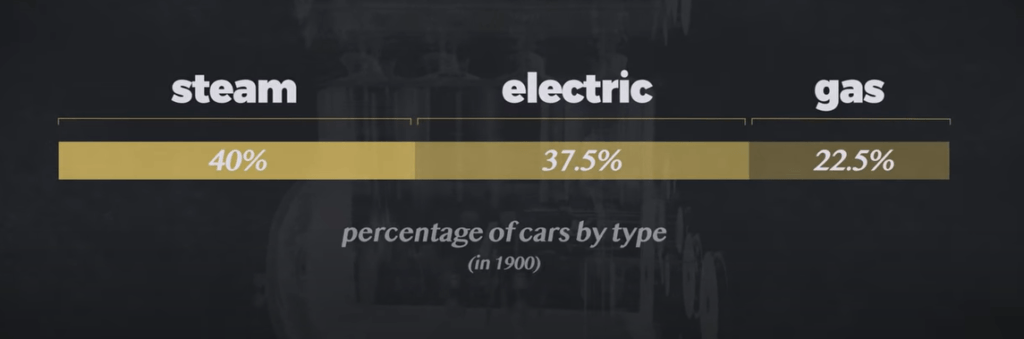

By 1900, there were 4,192 vehicles on the streets of the US. Steam cars accounted for 1,681 of these; 1,575 were electric, and 936 had internal combustion engines.

If you wanted to get around town, the electric carriage was a better option – that is, if you were rich enough to afford one. Unlike internal combustion engines, electric vehicles were easy to turn on, accelerate, and brake, there was no exhaust, and you didn’t have something constantly exploding under your seat. Oh, and you also didn’t have to crank the engine every time you stopped, which is part of the reason that electric Studebaker won the Philadelphia race so handily. As a result of this ease of use, electric cars were looking like big business in the early 1900s, especially for the industry giant Electric Vehicle Company.

At the time, the Electric Vehicle Company was the biggest car manufacturer in the country, and they used a model that seems revolutionary now, but made sense back then. Instead of selling their cars, they rented them to people for one or more days. Each night the renter could return the car to a central garage where the Electric Vehicle Company would charge and service the vehicle – a model very similar to how stables worked at the time.

But despite the electric car’s success, its golden age was about to end.

First, an investigation by The New York Herald accused the Electric Vehicle Company of fraudulently securing a loan, leading to intense backlash that ultimately bankrupted the company in 1901.

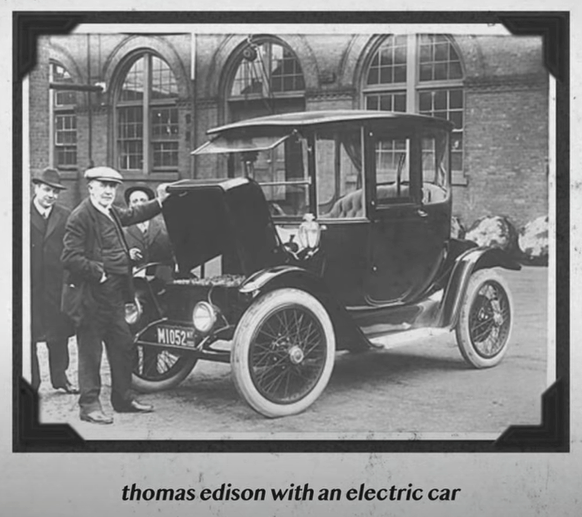

Then, Henry Ford started banging out gas-powered vehicles, and with the help of scale, exploitation of his workers, and the invention of the electric starter in 1912 (which meant that drivers no longer had to crank their cars every time they wanted to travel), people started paying attention to the internal combustion engine. Around the same time, roads were beginning to be paved – but they took people out into the country, which lacked charging ports, so electric vehicles’ range became more of an issue.

Local and federal governments failed to build the infrastructure necessary for electric vehicles, meaning that gas-powered vehicles were a much better option for the growing hordes hoping to escape the city.

And finally, as the auto industry began to attract more customers in the early 1900s, advertising became increasingly gendered. Electric vehicles, more often than not, were sold to women as easy-to-drive parlors on wheels. Even Henry Ford’s wife owned an electric vehicle.

Gas-powered cars, on the other hand, were painted as dirty, greasy, powerful, and masculine cars that could take you out to the country and let you speed through the streets. So, white men, aka those who had both money and power in early 20th century America, aka the primary car-buyers, tended to purchase gas-powered vehicles. 👆

And so, by the 1920s, the perfectly serviceable electric car was all but extinct. These cars failed not because they were inferior vehicles; they failed because cultural and societal pressures steered us into the driver seat of gas-guzzlers.

The EV1— Oh wait, never mind! (1990-2003)

The EV1: a revolution in the car industry. With California’s announcement of a zero-emissions car mandate, General Motors scrambled to make an electric car. Their answer was the 1996 EV1. A futuristic car (for the 90s), that could reach 80 mph on the highway and had a range of 70 to 100 miles, all on an electric battery.

The electric car was back! Tom Hanks grabbed one and loved it, and so did Danny DeVito. But GM wasn’t making this car because they cared about the environment, or about electric cars, for that matter. They made the EV1 because they had to.

The California Air Resources Board required the top seven auto-manufacturers to make 2% of its fleet emissions-free by 1998, 5% by 2001, and 10% by 2003. So, car manufacturers, GM included, initially complied: they retrofitted their models with electric motors and sold them throughout California.

Initially, it seemed like the auto-industry was going to make a momentous change – that is, until people started looking under the hood.

While GM was leasing their EV1s to the likes of Tom Hanks, they were also mounting lobbying, advertising, and astroturfing campaigns to dismantle the zero-emissions mandate. 👀

Why, you may ask?

Well, consumer advocate Ralph Nader thinks it’s pretty simple:

“The executives at the top, their motto seemed to have been, ‘Going backwards into the future.’ And that’s what they’ve been doing for decades.”

Despite consumer demand, and large waitlists for the EV1, GM actively sought to dismantle EV production, because it was inconvenient for them. Keep in mind, this was around the same time when they started selling SUVs and Hummers en masse. So, they not only successfully got the California Air Resources Board to repeal the mandate, but afterwards GM rounded up every EV1 they had leased out, took them to a junkyard, and crushed them.

That’s right: GM the company that just ran this Super Bowl ad had a successful electric vehicle program in the early 2000s, but they purposefully tanked it because they wanted to sell more SUVs, Hummers, and gas vehicles.

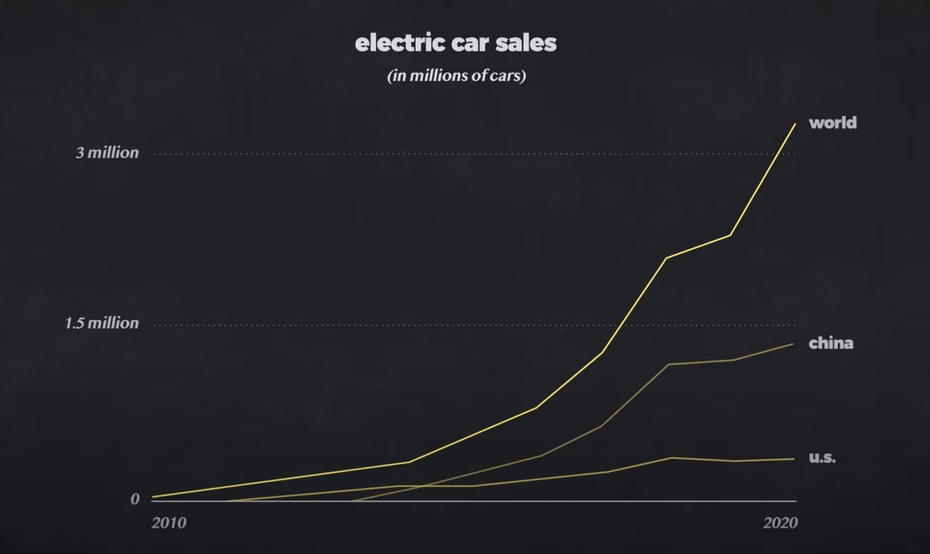

The electric car revolution? (2010-2021)

Are things different now, in 2021? Or will we repeat the same mistakes?

If Tesla’s and other electric vehicles’ trajectory are any indicator, EVs might be here to stay. If and how quickly they replace gas-powered cars seems to be up to strong government policy. Policy which, until November 23rd, 2020, GM was ruthlessly opposing. Their flip-flopping might just have something to do with the fact that Trump is no longer in the White House.

In fact, throughout Trump’s presidency, the auto industry fought tooth and nail to prevent any emissions standards.

👉 In March of 2020, Trump, with the support of auto industry giants, rolled back a landmark Obama-era emissions mandate. The rollback would’ve led to nearly a billion additional metric tons of CO₂ in the atmosphere, if not for Biden’s reinstatement of the order.

Much like California’s zero-emissions mandate in the early 2000s, GM was right there on the ground lobbying for that rollback to happen. The National Auto Dealers Association, which GM works closely with, has spent over $57 million lobbying congress since 1998.

The reality is that emissions mandates and electric car subsidies do work, but while great for us, they force the auto industry to do away with their “backwards into the future” mindset.

But, it is possible to rapidly ramp up electric vehicle use; Norway is a perfect example.

In 2012, 3% of the country’s new cars were electric; just seven years later, that number is up to 56%. What Norway did was quite simple: 📌they subsidized EVs heavily, to the point where they were cheaper than their gas-powered counterparts, and 📌 they built a charging infrastructure to support these new cars.

It does seem like the US is starting to follow suit, with California’s governor issuing an executive order banning gas-powered car sales by 2035, and GM saying that by that same year it will sell only electric cars.

While this is hopeful news, considering the history of the auto-industry it’s hard to fully embrace these announcements without some skepticism.

Are electric cars actually the best solution? (2021-2050)

As we move closer and closer to 2050, the year when the world must be at zero emissions to avoid the worst climate change scenarios, it’s important to take a step back and consider whether switching to electric cars is the best solution.

No, we shouldn’t stick with the internal combustion engine; we should be trying to replace our current cars with electric models, but while also envisioning a world with fewer cars. Because, to be honest, cars suck.

Co-founder of Zipcar, Robin Chase, sums up the failed promise of cars perfectly in a documentary on CuriosityStream: “We were promised that cars brought independence, and that probably was true in the 30s, 40s, 50s – but we all know that most of our driving is in very dense traffic. It’s not a pleasure, it’s very expensive, and time-consuming.”

👉 Even electric cars have an impact, both in terms of emissions and the green colonialism and exploitation that accompanies corporate desires for metals like lithium.

So when we begin to support new infrastructure for charging systems, we also need to consider how to build cities and towns that no longer center cars as a resident’s primary mode of transportation, instead making walking, biking, and using public transit really easy, really pleasurable, and really cheap (or free).

The key question should be, ‘How can we connect countries, states, cities, and towns through affordable and clean public transportation, without cars?’

Yes, the electric car will have some role to play in this new transportation system, but it should be seen as a piece of the puzzle rather than the essential tool that unlocks travel.

Creating this alternative transportation system will certainly be difficult. But not only is it possible – through militant community organizing and consistent public pressure on corporations, politicians, and governments – it is also an essential part of a more ethical, more just, zero-emissions world.

Leave a Reply