Curries. Burgers. Sushi. Pizzas. Tortillas. As a species, food is central not only to our survival but also to our cultures. We love food. But as much as we love food, we also love to throw it away.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that globally almost one third of food produced for consumption never gets eaten. And in the US that number is even higher.

👉 Forty per cent of the US’s available food supply gets wasted every year. As a report from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) notes, that’s like buying five bags of groceries at the store and then just leaving two of them in the parking lot every time you shop.

Our Changing Climate series

This post is part of a new series created by ethical.net in partnership with Our Changing Climate: an environmental YouTube channel that explores the intersections of social, political, climatic, and food-based issues. Get early access and support this important research by becoming a Patreon.

Today we’re going to look at food waste with three questions:

- Why is excessive food waste happening?

- What are its environmental consequences?

- And how can we fix it?

👉 If all the food currently getting thrown into the landfill every year was instead diverted into meals for those in need, we’d be able to feed as many as 1.8 billion people.

👉 On top of that, food waste has been estimated to be responsible for roughly 8% of global emissions. If it was a country it would rank third, under China and the United States for yearly greenhouse gas emissions.

So, food waste is one of many issues at the crossroads of climate action and social justice. Its large emissions footprint not only comes from all the energy needed to ship, process, and produce the food that ends up in the trash, but also from the potent methane fumes that food emits as it decomposes in landfills.

How Food Turns Into Trash

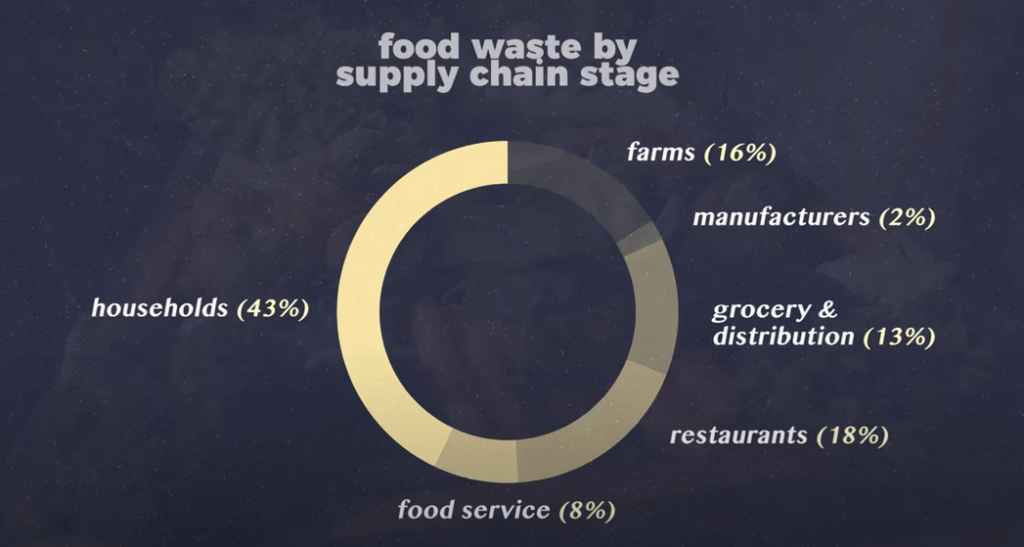

But food doesn’t just sprout out of the ground and then magically end up in the trash; there is a long chain of business and consumer interactions that at any point might turn perfectly edible food into waste. Simply put, food transforms into trash in two general areas as it travels from farm to plate:

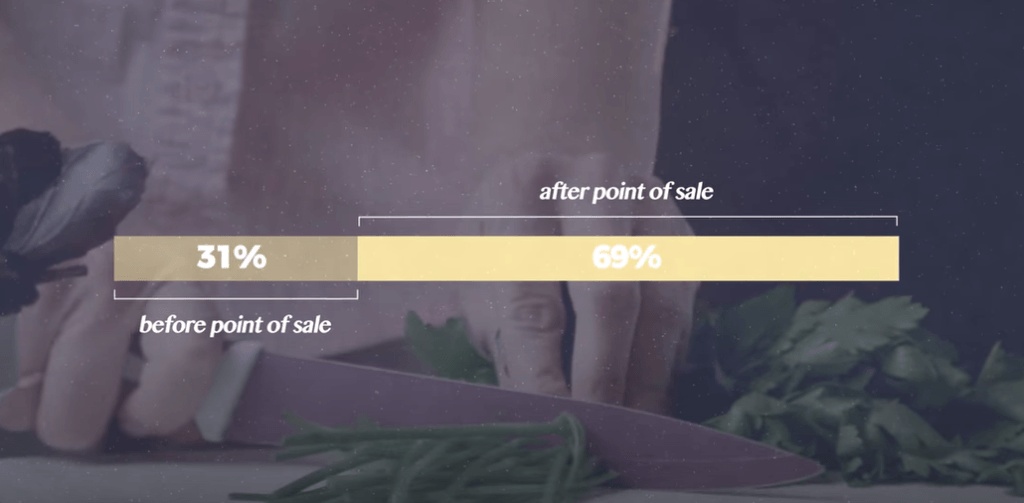

📌 Before the point of sale and after the point of sale.

If we look at this ☝️ chart, the majority of food waste generated in the United States comes after the point of sale, but let’s look at food loss before that – on farms and in grocery stores – in order to understand how this all starts.

Before I transitioned to making YouTube videos full-time, I worked in a number of food-related positions where I saw first-hand how the drive for perfect, abundant produce perpetuated an unnecessary trend of food waste.

As a farmhand at a number of different farms, when I saw insect bites on arugula leaves or blemishes on peppers and tomatoes, I knew they were destined to rot. All that time, effort, and fuel wasted because the farm manager knew that better-looking produce will always sell over imperfect ones.

These ‘cosmetically challenged’ products, as they’ve come to be known, can often end up left on the ground by harvesters or even make their way to landfills, adding to piles of food that decompose and generate harmful emissions. But the aesthetics of produce are just one part of the picture. Market prices for food can also affect whether crops make it through the harvest.

According to one recent study that analysed on-farm food loss in California, 33.7% of produce remains unharvested every year. That’s the equivalent of growing 300 acres of cantaloupe and leaving 100 acres of it to decay in the fields – which, according to an article from Civil Eats, is exactly what happened to sixth-generation farmer Cannon Michael.

Michael couldn’t “justify paying workers to pick [the cantaloupe] because the cost of labour, packing, and shipping would have been more than the price he could get for the fruit.”

The Illusion of Abundance

And even if the food does make it off farms, it still has to navigate the gauntlet of grocery store aisles. One of the best ways to sell food is through the illusion of abundance. People shop visually, and to most, that last apple on the shelf was left there because there was something wrong with it, not because it just happened to be the last one.

In order to appear abundant, grocery stores often overbuy food to trick people into purchasing items. As a result, produce inevitably goes to waste as it sits out all day like glorified window dressing.

Farmer Delaney Zayac explains this dilemma in the documentary Just Eat It:

“If this was what I had and there was an hour left in the market, that one bunch of chard would sit there, and no one would buy it. But if I had 30 bunches of chard all bursting out I’d probably sell 25 bunches of chard.”

So at the grocery store and farmers markets, vendors face an uphill battle against the old saying “Pile it high and watch it fly.” They need to produce an excess of food to sell their goods, but that excess can at times lead to more waste.

After the point of sale, the plague of food waste continues. Indeed, household, restaurant, and food service waste accounts for 69% of the United State’s annual food waste.

As a consumer and lover of food, I’ve tried hard to minimise my waste, but it can be easy to cook or buy excess that ends up in the compost or trash.

For a family of four, household food waste costs $1,800 (£1,430) annually, and with the average plate size expanding by 36% since 1960 and with refrigerators growing 30% in volume since 1972, it’s tempting to buy more food just to fill up the space.

Overbuying, and the inevitable ‘cleaning out the refrigerator activity’ that comes with it, can also be attributed to buy-one-get-one promotions or purchasing in bulk.

Our appliances, supermarkets, and even our plates are all nudging us to buy more. In addition to overbuying, in the United States there is also a severe lack of clarity when it comes to dealing with expiration dates and spoiled goods.

Sell-By or Expiration Dates

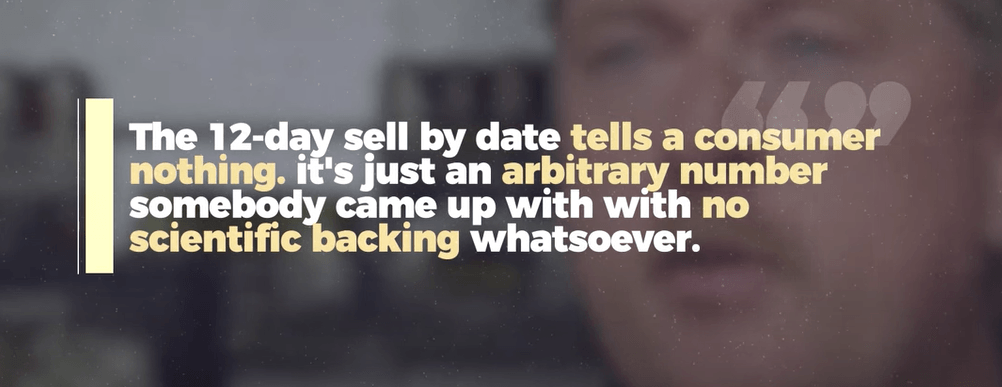

There are no federal laws regulating sell-by or expiration dates. As a result, labels can mean basically anything depending on where you buy your food. In Missoula, Montana, for example, milk’s sell by date is set at 12 days after pasteurization, even though the standard is 21 to 24 days. That’s because, in most cases, these dates are set by the milk producer and not a regulatory service.

As one grocery vendor in Missoula laments, “the 12-day sell by date tells a consumer nothing; it’s just an arbitrary number somebody came up with, with no scientific backing whatsoever.”

This lack of clear information regarding when a product actually goes bad means that households throw out perfectly edible food well before it expires.

In short, there are marketing, labelling, cultural, and psychological forces all coming to play in order to make food waste a large problem in the United States.

How Can We Fix Food Waste?

Ultimately, there are many vectors by which food becomes waste, whether in your own home or even before it makes it onto a grocery store shelf. But there is hope. There are very tangible solutions to these problems at all levels of the supply chain. At the individual level, solutions look like creating a plan to use all the food you buy, or using sites like Eat by Date to truly understand whether your food has expired, and then composting it instead of throwing it in the trash.

You can even get involved with groups like Food Not Bombs, which has local chapters all over the world that recover food from local restaurants and stores and give it to those in need.

📌 On the supply side, solutions look like reducing food demand by eliminating buy-one-get-one promotions, donating food that’s not fit for sale, or even using boxes and props to maintain the illusion of abundance without needing excess produce.

📌 And on a policy level this means actions like standardising expiration dates to accurately reflect the science behind foodborne illnesses. Food waste is a preventable problem, and addressing food waste means tackling both climate change and hunger in the process.

We don’t necessarily need fancy farming technologies to create more food for people who go hungry; we need to work together on every level to more equitably distribute the resources we already have, and in doing so we not only mitigate climate change, but also create stronger communities.

Watch the video essay here ⤵️

Resources:

1. ‘Reduced Food Waste’ (Project Drawdown)

2. Food Waste Is the World’s Dumbest Problem (Vox via YouTube)

3. ‘27 Solutions to Food Waste’ (ReFed)

4. ‘A Holistic Approach to Reducing Food Waste’ (NRDC)

5. ‘Food Wastage Footprint & Climate Change’ (FAO)

6. ‘Consumer Choice and Food Waste: Can Nudging Help?’ (Bolos et al.)

7. Just Eat It: A Food Waste Story (Grant Baldwin via YouTube)

8. ‘Key Characteristics and Success Factors of Supply Chain Initiatives Tackling Consumer-Related Food Waste – A Multiple Case Study’ (Aschemann-Witzel et al.)

9. ‘About Food Waste’ (Move for Hunger)

10. Expired? Food Waste in America (via YouTube)

11. ‘Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill’ (NRDC)

12. ‘The Progressive Increase of Food Waste in America and Its Environmental Impact’ (Hall et al.)

13. ‘Study Finds Farm-Level Food Waste is Much Worse Than We Thought’ (Civil Eats)

14. ‘On-Farm Food Loss in Northern and Central California: Results of Field Survey Measurements’ (Baker et al.)

15. ‘Refrigerators and Freezers’ (Appliance Awareness Standards Project)

16. ‘Reducing Food Loss and Waste: Setting a Global Action Agenda’ (World Resources Institute)

17. ‘Portion Size Me: Downsizing Our Consumption Norms’ (Wansink & Van Ittersum)

18. Eat By Date

Leave a Reply